Complex Historic Town Core

Summary of Dominant Character

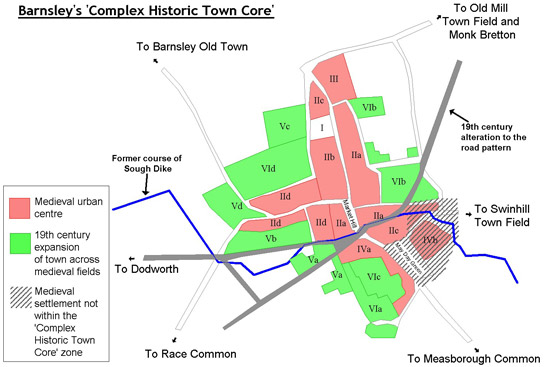

This zone includes most of the historic settlement of Barnsley town, as shown on the 1777 parliamentary enclosure map (Fairbank 1777), excluding areas that have been significantly redeveloped in the 20th century. Barnsley town displays a more complex urban form than settlements within the ‘Nucleated Rural Settlements’ zone. The medieval settlement was laid out in a well-planned manner and included a medieval market that gained its market charter in 1249 (Elliot 2004, 168). The town significantly expanded in the 19th century and most of the buildings within the historic core date to this time. There has been some 20th century alteration in the northwest and southeast of the zone but the plan form of the medieval settlement is fairly well preserved.

Relationship with Adjacent Character Zones

Barnsley’s historic core has been circled by later development. The initial expansion of the town consisted of terraced courts, which have mostly been demolished but which led on to the development of large areas of terraced housing. The ‘Grid Iron Terraced Housing’ zone forms a near complete ring around the town centre, except in the south where former terraces have been replaced by later municipal housing and in the north where larger elite residences were established in the ‘19th to Early 20th Century Villa Suburbs’ zone.

The ‘Complex Historic Town Core’ zone also has a key relationship with the ‘Late 20th Century Replanned Centres’ zone, which forms a ‘u’ shaped band south of the historic centre. This latter zone is one of dramatic alteration to the landscape and little former historic character is legible in this area. The medieval core of Barnsley mostly lies outside this area of major redevelopment. However, east of Cheapside the modern market developments cover part of the historic core around the former May Day Green. Here the road pattern and building layouts overwrite the 18th century, and possibly earlier, developments.

Figure 1: Map showing the assumed layout of medieval Barnsley. See 'Plan Form Analysis' for explanation of numbering.

Based on OS mapping © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007

Plan Form Analysis of Barnsley’s Historic Core

The layout of the historic core of Barnsley survives well, with many earlier road patterns remaining. Through a combination of historic map analysis, consideration of archaeological excavations, and comparison with other medieval settlements, the historic core has been divided into areas inhabited in the medieval period and those that were subject to 19th century development (see Figure 1 above). The phased development of the town is outlined below, with degrees of historic legibility and later development considered in each plan unit.

Plan Unit I

The original settlement of Barnsley, located to the north west of the current centre at an area now known as Old Town, is likely to have had Saxon origins (Elliot 2002, 26-27). This settlement was of no particular import and was only recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 under Keresforth. In 1156 the manor was granted to the Cluniac priory of St John at Pontefract and the town was relocated to its current position by the 13th century. This new position took advantage of better communication routes, including the road between Wakefield and Sheffield and the major highway between Richmond and London (Hey 1979, 57). There is no archaeological evidence for settlement on the site of the planned medieval town prior to the establishment of new Barnsley.

The church of St Mary’s would have been an important feature of this new settlement. The current building was rebuilt in 1862, apart from the tower, which had been built in 1821 (Yorkshire Archaeology Society 1897, 332). Prior to this redevelopment, the building had been described in a 19th century edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine as a “beautiful piece of Norman work” (cited in Hey 1979, 57). The remains of this medieval structure are found in fragments of medieval grave covers that were built into the current church (SYAS 2008).

Plan Unit II

The new settlement was laid out in a characteristic medieval form, with narrow plots running perpendicularly to the main street and a system of back lanes surrounding the urban plots. The town was centred on a wide open market place at Market Hill and the monks were awarded a market charter in 1249 for weekly Wednesday markets and an annual fair (Elliot 2002, 27). The transport routes coming from the north of the town will have been directed through this new market place.

Early maps of the town show a concentration of buildings immediately around the market place. To the west of Market Hill the plots are very short but those on the east of the market seem to be extra long. These may have been extended to compensate for narrow frontages. Archaeological work would be required to know whether the tenements along Shambles Street were contemporary with the rest of the settlement or whether they overwrote enclosed plots to the rear of the buildings west of Market Hill. Possible evidence for the later establishment of Shambles Street can be seen in the reverse ‘s’ shape of some of these plots. This suggests that they were developed from part of the town’s open field, which would have been ploughed in this characteristic pattern.

Early examples of timber-framed buildings have been found along Church Street, dating to the 15th and 16th century (Belford and Hayling 1999, 18; Tyer 2002, 5). By this time Barnsley had developed into a sizable community compared with other settlements in the Wapentake of Staincross (Elliot 2002, 27). This is supported by evidence for a timber yard in Barnsley in the 15th century supplying building materials to a booming local economy (Tyer 2002, 5).

Figure 2: Part of the historic core of Barnsley showing the long narrow plots surviving in the current townscape.

1893 OS mapping © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024 overlain by Cities Revealed aerial photography © the GeoInformation Group, 2002.

IIa: Within this area there is clear survival of the long thin plots facing onto Church Street and Market Hill. Most of the buildings within this area date to the 19th century and, particularly around Market Hill, consist of commercial buildings. However, an early school building, founded by Thomas Keresforth in 1660, survives (Lawson 1840, 227) and is now used as an art gallery and adjoined by the College of Art and Design.

The market place and parts of the town were redesigned in around 1823 by John Whitworth (Whitworth 1998, 192), at around this time Eldon Street was built, cutting through the former road pattern and shortening the tenements running out from Market Hill. The Moot Hall, a former meeting place, council chamber and law court, was also demolished. This ancient building of unknown origin consisted of a large upstairs meeting room above several shops (Jackson 1858, 127-135).

IIb: The pattern of thin tenements doesn’t survive as well in this area although the road pattern is still in place. This is due to the building of the Town Hall and Barnsley College in the 1930s. The land was cleared of dense terraces and courts as well as Barnsley Old Hall, which was the former Manor House.

IIc: In the In the 1960s, much of the commercial centre of Barnsley was redeveloped to create large shopping centres. The cattle market and buildings south of Eldon Street were subject to considerable alteration but, unlike developments further to the south and east, the road pattern was maintained.

IId: Shambles Street was largely rebuilt after the establishment of the 1822 Barnsley town improvements act, under the designs of John Whitworth (Whitworth 1998, 192). This phase of rebuilding maintained the long thin tenement pattern but this was not to survive the mid 20th century redevelopment of the town. Large numbers of public and municipal buildings were built across this area within the main road pattern but removing the individual plots.

Plan Unit III

This area consisted of more irregular plots to the north of the main town. This land was outside the medieval back lane and is likely to have been a later expansion of the settlement. Historic maps show at least one large private house in this area. This may be an early example of the trend seen in the 19th century for more well off members of the community to position their homes away from the industrialised areas in the south of the town.

This land is now filled by the mid to late 20th century Barnsley College buildings. The main road pattern remains but the former character of the area is not visible.

Plan Unit IV

May Day Green was the site of fairs and markets in Barnsley for many generations and until the 19th century bull and bear baiting took place on this land (Jackson 1858, 126). This land was likely to be held in common in the medieval period but small works and cottages were encroaching upon the green from at least the 18th century (Fairbank 1777). This is likely to have started as illegal ‘squatter’ settlement on the common and developed into an industrialised area.

IVa: This area is now part of the commercial core of Barnsley. The buildings were redeveloped in the mid to late 20th century but the road pattern and general layout of the plots survives.

IVb: Although outside of the ‘Complex Historic Town Core’ zone, this area is included within this analysis because it was part of the early settlement. In the 19th century the town steadily expanded to fill this land with larger industrial developments, including a gas works and several iron foundries. These were cleared in the 1970s to make way for indoor and outdoor markets and a shopping centre. The current landscape shows no evidence of these industrial developments or the earlier urban patterns.

Plan Unit V

In 1249 a charter was granted to the town allowing "one fair day lasting for four days, viz., the eve of Saint Michael's day and two days hereafter.." (cited in Elliot 2004, 168). The land adjacent to this park was still known as Fair Field into the 20th century and this area was probably set aside for this purpose from medieval times. The Fair Field was part of the land enclosed from former open fields by the 1799 Parliamentary Enclosure Award (date from English 1985); an extension to the graveyard of St Mary’s Church reduced the field’s size in 1806 (Lawson 1840, 226). The field pattern established as part of the parliamentary enclosure award influenced the regular shape of the graveyard. This pattern is still visible in the modern public park.

Plan Unit VI

Much of this area was part of the open field system in the medieval period. Some of the land was enclosed into narrow reverse ‘s’ shaped fields in the late medieval or early post-medieval period, with the remaining townfields and commons around Barnsley enclosed as part of the 1779 Parliamentary Enclosure Award (English 1985).

As the industrial wealth of Barnsley allowed expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries, the town was to expand over these former fields. Often the landowners that benefited from the Parliamentary Enclosure Award were also industrialists. They took the opportunity to amalgamate former disparate land parcels and use this land to build industrial sites and housing for the workers required to operate them. Several linen mills and a calendering works, where cloth was “pressed under rollers for smoothing or glazing” (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 1973), were established in the west of the town and large numbers of terraces and courts were built for the textile workers in the south west of the town.

As mentioned above, the 1820s saw the laying of new roads at Eldon Street, Pitt Street and Peel Street (Whitworth 1998, 191-5). These new road patterns formed the framework for the new housing and industrial sites.

VIa: In the 1840s there were large numbers of weaving cottages within this area, with most buildings having between 2 and 3 looms per cottage (Taylor 1995, 43). These would have been linen weaving cottages with basement workshops. There was also a timber yard marked on 1893 maps. These buildings were replaced by late 19th/ early 20th century shops as the wealth of the town increased and commercial developments became more established. Part of this land had been enclosed in strips prior to the Parliamentary Enclosure Award and there is still the curve of this field pattern in the layout of Wellington Street.

VIb: The current character of this area dates to around the same time as VIa but this land was never utilised for industrial development. Much of this area was established initially as a commercial and cultural zone, with the building of large town houses, a Victorian shopping precinct and the Civic Hall in the mid 19th century. The pattern of the narrow medieval tenements associated with the housing along Market Hill and Church Street is still visible in this area although that pattern was disrupted by the creation of Eldon Street.

VIc: This area had a very similar formation history to plan unit VIa until the 20th century. At this point the commercial buildings were largely replaced with modern shops, the general layout of the street pattern, however, remains. This has also preserved the curving pattern of strip fields that predated the establishment of weaving workshops.

VId: Taylors Mill dominated the land south of Shambles Street in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The linen manufacturing business was founded in 1727 and the mill opened the Peel Street Mill in 1845. By 1870 it was reputed to be the largest of its kind in the country but by 1939 the firm relocated to Ireland and the site closed (SYAS 2008). The mill was built on the edge of the medieval centre and largely overwrote the former enclosure pattern.

The development of terraced houses north of Westgate was broadly contemporary with the establishment of the mill. These houses were established on fields enclosed from Barnsley’s open town fields as part of the 1799 Barnsley enclosure award (date from English 1985) and the housing fitted within the regular field pattern.

Both of these areas have been subject to substantial alteration in the late 20th century. North of Westgate, the Police headquarters and Magistrates court removed most of the small terraces, south of Shambles Street, the mill site was demolished to make way for modern supermarkets. Remnants of the 19th century buildings do however remain in both of these areas.

VIe: This land was also utilised by industry in the 19th century. A small linen calendaring works is known in this area from 1810 and this mill was later enlarged by the Spencer family and used for cotton spinning, weaving, calendering and printing. The downturn in the textile industry in Barnsley in the late 19th century saw the closure of this site, with the weaving shed used as an engineering works. In the First World War shells were produced here and by 1919 the works was owned by the Barnsley Canister Company. These buildings survived until 1992 (ASWYAS 2000) and the site remained as scrub for some time. The modern expansion and redevelopment of central Barnsley is likely to include the development of this disused land in the near future. The road pattern along the edges of this site is likely to date back to the medieval establishment of Barnsley, a pattern that will continue to be visible despite alteration to structures on the site itself.

Character Area within this zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Barnsley Historic Core (Map)

Bibliography

- ASWYAS

- 2000 Barnsley Town Centre Link Road, South Yorkshire. ASWYAS 806 [unpublished].

- Belford, P. and Hayling, N.

- 1999 Archaeological Watching Brief and Standing Building Recording at 1-5 Church Street Barnsley, South Yorkshire. ARCUS 393 [unpublished].

- Elliot, B.

- 2002 Glimpses of Medieval Barnsley. In: B. Elliott (ed.), Aspects of Barnsley 7. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books, 23-38.

- Elliot, B.

- 2004 The Making of Barnsley. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books Limited.

- English, B.

- 1985 Yorkshire Enclosure Awards. Hull: University of Hull.

- Fairbank, W.

- 1777 A Map of the Township of Barnsley in the Parish of Silkstone. Available from: Barnsley Archives, Reference: EM/1953.

- Hey, D.

- 1979 The Making of South Yorkshire. Ashbourne: Moorland Publishing.

- Jackson, R.

- 1858 The History of the Town and Township of Barnsley, in Yorkshire from an Early Period. London: Bell and Daldy.

- Lawton, G.

- 1840 Collectio rerum ecclesiasticarum de diœcesi Eboracensi; or Collections Relative to Churches and Chapels within the Diocese of York. London: J.G.F and J. Rivington.

- SYAS

- 2008 South Yorkshire Sites and Monument Record [dynamic MS Access – GIS database] Sheffield: South Yorkshire Archaeology Service. Available by appointment with SYAS, Howden House, 1 Union Street, Sheffield, S1 2SH. Email: syorks.archservice@sheffield.gov.uk [accessed 07/05/08].

- Taylor, H.

- 1995 Taylor Row and the Handloom Weavers of Barnsley. In: B. Elliott (ed.), Aspects of Barnsley 3. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Publishing, 39-64.

- Tyers, I.

- 2002 Dendrochonological Analysis of Timbers from 41-43 Church Street, Barnsley, Yorkshire. ARCUS 574t [unpublished].

- Whitworth, A.

- 1998 John Whitworth, Architect and Surveyor of Barnsley. In: B. Elliott (ed.), Aspects of Barnsley 5. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Publishing, 189-200.

- Yorkshire Archaeological Society

- 1897 Notes on Yorkshire Churches. In Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 14.