Agglomerated Enclosure

Summary of Dominant Character

This zone dominates the east of the Barnsley district. Fields within the zone are predominantly used for large-scale intensive arable farming. This has been the cause of significant loss of field boundaries in the late 20th century, as they are removed to agglomerate fields – creating larger agricultural units. The remaining field boundaries are a mix of hedgerows and fence lines, sometimes with fences supplementing gaps in poorly maintained hedged boundaries.

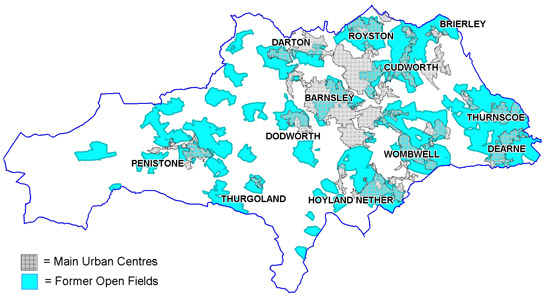

Despite this boundary loss, closer examination of this zone reveals a history of an agricultural landscape planned in the medieval period, or earlier, and based on the medieval common arable system. Evidence for this earlier history includes field boundaries and surviving road patterns that exhibit the characteristic sinuous curves of former open fields. 67% of the land within this zone is recorded as former open fields, making this medieval agricultural technique a significant part of the inherited character of the zone; this will be explored further below.

Relationships with Adjacent Character Zones

There is not always a clear distinction between the enclosed landscapes of the ‘Agglomerated Enclosure’ zone and those of the other rural zones. There has been some boundary loss within all of the rural zones, but this has generally occurred on a less significant scale than in the agglomerated enclosure zone. This is in part due to the different land uses in the west and east of the district. Sheep rearing is a significant farming industry around Penistone in the west, but much of the lower land in the east has retained its arable use, with modern farming methods leading to boundary removal.

There are small areas of ‘Surveyed Enclosure’ and ‘Assarted Enclosure’ interspersed with the main ‘Agglomerated Enclosure’ zone in the east of the district. These represent small areas of common land that were enclosed in the 18th and 19th centuries and remnants of ancient woodland that was not drawn into the open field systems that developed in the medieval period. These more marginal lands have suffered less boundary loss through agricultural intensification in the 20th century than the surrounding agglomerated enclosures; this is likely to be a result of the poorer quality soils and marginal positions of these areas.

In the 19th and 20th centuries local coal seams were intensively exploited and significant extractive and former extractive landscapes exist in close proximity to this zone – sometimes as islands within it.

Inherited Character

The field patterns visible on 19th century mapping for this zone suggest that most of the enclosed land at that time had developed from the open fields surrounding nucleated villages. This medieval farming system consisted of large open areas of land cultivated in long thin unhedged strips that were “individually owned but farmed in common” (Taylor 1975, 71). The land would be ploughed into ridges by oxen and often the practice of turning the plough team at the end of each strip would produce a characteristic reverse ‘s’ shape (ibid, 78-80).

Within the open field system, ownership of strips of land was scattered throughout the common fields. This meant that people could own a mixture of the good and bad soils. This pattern of land ownership made communal farming necessary, as strips within the same unhedged area could not be used for corn whilst others were turned to fallow and grazing. There were typically three large open fields of strips that could be farmed in rotation (a pattern common across the English Midlands) (Hall 2001, 17). This pattern of land use was only partially developed in the west of the district, but within the area covered by this zone there were substantial open fields that ran right up to the limits of the township boundaries. The field systems around Thurnscoe, Bolton-Upon-Dearne, Brierley and Cudworth are good examples of this.

From the 15th century onwards, farmers were exchanging dispersed strips throughout the open field to obtain contiguous blocks of land that could be enclosed (Rackham 1986, 170). This often led to the patterns of strip fields seen on 19th century maps in this area and in places these patterns survive quite well despite modern agglomeration. Even where the pattern of strips themselves does not survive, the road patterns’ indicate the origins of the agglomerated fields; the roads’ sinuous courses fossilise the edge of former strip fields.

Figure 1: Land recorded by the project as former Open Fields.

Based on OS mapping © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007

Figure 2: Billingley village and surrounding strip enclosures.

Cities Revealed aerial photography © the GeoInformation Group, 2002 overlain by 1854 OS mapping © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024

Just south of Brierley there is a conspicuous gap in the otherwise open field agricultural landscape. This was the location of Brierley Deer Park, another medieval feature that is still partially legible within the layout of this zone. In 1280 a grant of free warren is recorded for Brierley (Hunter 1831, 402). It is uncertain if this is the date of the establishment of the park, if not it was certainly in place by 1424 when Sir William Harryngton owned the manor of Brierley (Harrison & Watson 2006). Within the park, and still surviving as a scheduled earthwork, is the moated site of Hall Steads, which served as the manor house. A bank north of West Haigh Wood was formerly part of the park boundary. There has been substantial boundary loss across the former park, resulting in the area being recorded as agglomerated fields rather than as part of the ‘Private Parkland’ zone.

This zone also shows the influence of the extractive industries of the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Both ‘Cawthorne to Darton Town Fields’ and ‘Carlton and Royston Enclosures’ contain fossilised routes of railway lines that grew up around the mining industry in the mid 19th century. These lines often have a significant impact on the landscape because they survive whilst earlier hedgerows around them have been removed.

There are also surviving segments of the Barnsley Canal, which opened between Heath and the Barnsley Basin in 1799, with the remaining section connecting Barnsley to Barnby in 1802. Walter Spencer-Stanhope of Cannon Hall was the principal investor in the project and owned large areas of coal rich lands around Silkstone and Cawthorne that required a good transport route to make them profitable (Glister 1996, 215-6). Competition with newly built railways caused problems for the canal from the mid 19th century onwards. This, coupled with subsidence and breaching problems, led to the closure of the canal in 1953 (Barnsley, Dearne and Dove Canals Trust 2007). Much of the canal is now infilled but the course is often fossilised by surviving field boundaries and a stretch still in water runs through the ‘Carlton and Royston Enclosures’ area. The canal basin at Barnby has been more significantly altered; the basin and reservoir had been filled in and new houses built on the site by 1965 but the canal workers cottages survive.

Later Characteristics

The loss of boundaries, which has produced the open character of much of this zone, appears to have been most significant in the second half of the 20th century. The economies of scale provided to farmers by larger land parcels continue to offer incentives to remove hedges. Acting to counter this trend are incentives offered by the stewardship schemes sponsored by central government since the early 1990s. These schemes offer financial incentives to farmers who enter into environmental management agreements, which can include steps to maintain or restore historic features such as boundaries and buildings and (under the Environmental Stewardship scheme in place since 2005) reduce the impact of their activities on known buried archaeological sites (Rural Development Service 2005, 68-70). A contemporary development has been the introduction of the Hedgerow Regulations (HMSO 1997), which require the Local Planning Authority to be notified before the removal of a hedgerow. This allows a Hedgerow Retention Notice to be served, which can define hedgerows as important in historical, archaeological, wildlife or landscape terms.

Other late 20th – early 21st century influences on this zone relate largely to the influence of adjacent zones. Most notably new roads required by the need to link former ‘Industrial Settlements’ and ‘Planned Industrial Settlements’ to larger urban centres and places of work. These generally sever earlier previously coherent landscape units into smaller new ones.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Carlton and Royston Enclosures (Map)

- Cawthorne to Darton Town fields (Map)

- Cudworth Strip Fields (Map)

- Dodworth Open Fields (Map)

- Great Houghton to Bolton Agglomerated Fields (Map)

- Howbrook Agglomerated Fields (Map)

- Pilley to Wombwell Agglomerated Fields (Map)

- Shafton and Brierley Enclosures (Map)

- Stairfoot Enclosures (Map)

Bibliography

- Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council

- 2002 Barnsley Biodiversity Action Plan. Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council.

- Barnsley, Dearne and Dove Canals Trust

- 2007 Barnsley, Dearne and Dove Canals Trust [online]. Available from: www.bddct.org.uk/home.html [accessed 9/03/08].

- Glister, R.

- 1996 The Conception and Construction of the Barnsley Canal. In: B. Elliott (ed.), Aspects of Barnsley 4. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Publishing.

- Hall, D.

- 2001 Turning the Plough. Midland Open Fields: Landscape Character and Proposals for Management. Northampton: Northamptonshire County Council and English Heritage.

- Harrison, M. and Watson, M.R.

- 2006 Brererley, A History of Brierley [online]. Available from: www.brierley59.freeserve.co.uk/index.htm [accessed 9/03/08].

- HMSO

- 1997 The Hedgerows Regulation. (Statutory Instrument 1997 No.1160).

- Hunter, J.

- 1831 South Yorkshire: the History and Topography of the Deanery of Doncaster in the Diocese and County of York. Volume II. London: Joseph Hunter / J.B. Nichols and Son.

- Rackham, O.

- 1986 The History of the Countryside. London: J.M. Dent.

- Rural Development Service

- 2005 Higher Level Stewardship.

- Taylor, C.

- 1975 Fields in the English Landscape London: J.M Dent.