Private Parkland

Summary of Dominant Character

This zone consists of land used as ornamental parkland from the 17th to the early 19th centuries. These areas of parkland often have clearly defined boundaries, separating them from the surrounding countryside, in the form of circuit walls or plantation woodlands that provide both screening and enclosure. In some cases these boundaries are broken or absent, where agricultural use has been reintroduced within the park. Most of the larger parks developed from deer parks, so the boundaries often have deep internal ditches to prevent deer leaving the enclosed space.

Trees and woodlands are an important feature of most of these landscapes, with numerous ancient woodlands and deciduous plantations and scattered trees punctuating open areas. The surrounding ground cover is typically either permanent grassland, maintained as pasture, or land managed for arable cultivation.

The focal point for many of these parks is a large elite residence and related ‘home farm’ complex, sometimes on the fringe of an older village. Design features are generally intended to emphasise the high status of their owners. Such features can include ornate gateways and lodges; tree lined avenues and curving driveways; architectural follies, statuary, fountains and summerhouses; artificial lakes and ponds; formal gardens and kitchen gardens.

Relationship to Adjacent Character Zones

Areas of ‘Assarted Enclosure’ surround the majority of the ‘Private Parkland’ zone. This relationship may in part be due to the former wooded character of the land, as a link has been made between heavily wooded regions and high numbers of deer parks (Rackham 1986, 123). The later establishment of 18th century ornamental parklands within a similar area has more to do with the financial success of large landowners.

The parks are also often closely related to the ‘Nucleated Rural Settlement’ zone, with many examples abutting or surrounding historically older villages; a relationship that will be explored further below.

Inherited Character

Setting aside large tracts of land for the exclusive use of a small and powerful social group developed from the medieval tradition of creating enclosed deer parks. In their heyday, in the 14th century, it has been estimated that deer parks covered up to 2% of England (Rackham 1986, 123). This practice, in turn, was linked with designating an unenclosed hunting area, known as a forest or chase. All deer belonged to the crown, making a licence to create a park or chase, known as a grant of free warren, necessary from the 13th century (Jones 2000, 91). Numerous grant of free warren are recorded for the Barnsley area, only some of which resulted in the creation of enclosed deer parks. Medieval chases have not been considered within this zone as they rarely directly impacted on the physical form of the landscape.

Within the district of Barnsley the earliest known enclosed deer park was at Tankersley, with deer parks at Wortley, Wharncliffe, Gunthwaite and Brierley established by the 15th and 16th centuries. Of these, only ‘Wortley Old Park’ and ‘Wortley New Park’ remain as cohesive areas of parkland. Brierley was partly overbuilt by the industrial settlement of Grimethorpe; Tankersley was broken up after extensive ironstone mining and Gunthwaite was converted to agricultural use in the 18th century.

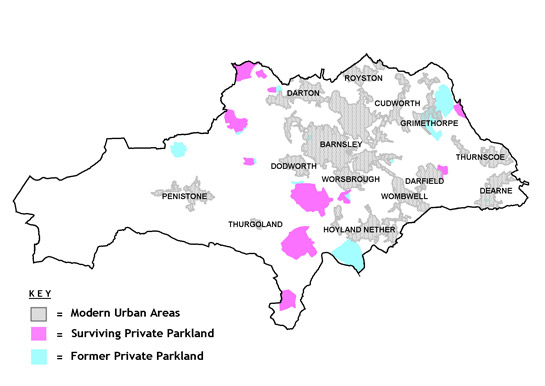

Figure 1: Map of the Barnsley district showing areas of current and former private parkland.

Based on OS mapping © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007

The enclosed space within a medieval deer park would have been too small for a true hunt. Rather, the parks were a store for fresh venison, other meats and timber (Rackham 1986, 125). Although medieval deer parks were an important economic resource for their owners, they nevertheless required considerable maintenance - representing significant investment in land resources. Most were being broken up by the 16th or 17th century as maintenance costs stretched their owner’s resources (ibid, 126).

Following the European renaissance of the 14th to 17th centuries, the idea of parkland was reborn as a focus for display of status and wealth, through the aesthetic manipulation and presentation of land. Initially such parks’ designs were influenced by continental models, based on the geometric division of space through the use of features such as low hedges; regular straight avenues of trees; and rectangular canals. During the 18th century this formal and geometric aesthetic was challenged by English landscape designers championing a naturalistic, picturesque approach to landscape (ibid, 129). Many of the earlier parks within this zone were re-ordered to conform to this naturalistic style during the 18th and 19th centuries. Stainborough Park, although itself an 18th century development, went through some of these changes in style. Early maps show a regimented layout of trees and pathways with formal ponds and gardens; many of these features were replaced, in the late 18th century, by rolling parkland and the development of the Serpentine Lake (Wentworth Castle and Stainborough Park Heritage Trust 2006).

In a number of cases within this zone, the sites chosen by landowners for their landscaped parks were already the sites of existing large houses and halls - in some cases the sites of medieval manor houses. Many of the earlier halls were entirely rebuilt in the 18th and 19th centuries, to conform to new architectural fashions and to create a more imposing symbol of wealth and status. At Worsbrough a 17th century manor house survives and at Birthwaite a 17th century structure partially survives, although remodelled, but in most cases there is nothing left of the earlier manor house.

Where these later parks relate to an earlier elite residence there is usually a close relationship with a nearby medieval nucleated settlement. The villages of Wortley, Worsbrough and West Bretton (over the border in West Yorkshire) are all closely associated with large parks and their halls. In some cases there is strong evidence for deliberate clearance of an earlier village or encroachment upon a village’s open fields during the creation of parkland; the sinuous field boundaries within Stainborough Park are suggestive of a former open field (associated with a village that no longer exists) and historic map analysis suggests that areas of open field were removed for the development of both ‘Wortley Old Park’ and ‘Cannon Hall’ park. There is also evidence for the re-routing of roads around new areas of parkland; this is known to have occurred at Cannon Hall.

The preservation of boundary and earthwork features from earlier agricultural landscapes by the 18th and 19th century park designers was partly a deliberate act – a way to root the new park in the landscape. As Rackham has pointed out, the designers of parklands set out to create, “an appearance of respectable antiquity from the start, incorporating whatever trees were already there” (1986, 129). This approach is most likely to have fossilised earlier steeply sloping ancient woodlands and boundary features along the edges of parks.

The fabric of buildings within nearby villages (see the ‘Nucleated Rural Settlement’ Zone) shows clear evidence of investment by estates in their appearance, through the rebuilding of tied cottages and facilities. This thorough reworking of existing rural forms has been associated by some authors (see Newman et al 2001, 105) with the park sponsors and designers desire to idealise the countryside, physically and historically separating it from the truth of its past. Examples of the establishment of ornamental features outside of the main park boundary are seen at Stainborough Park; at Rockley Abbey a former hall on the southern park boundary was remodelled to form a picturesque ruin. Follies were also built further afield in the surrounding countryside, as features to ride to; examples survive on the edge of Nether Hoyland and Worsbrough.

Later Characteristics

The resources needed to maintain these large tracts of land and their accompanying mansions appears, in most of the cases, to have been too great to maintain the parks in private use. Although outside this zone, Tankersley Park is a prime example of an absentee owner finding the mining of ironstone too tempting an economic prospect to disregard. This led to the breaking up and final abandonment of the park and hall (see ‘Surveyed Enclosure’). Cannon Hall also saw mining activity, although at a later date. This consisted of significant amounts of open cast coal mining after the Second World War, which led to much tree loss in the park (Moxon 2000, 158).

Most of the elite residences in this zone seem to have experienced major changes of use in the period 1900-1950. In the Second World War both Stainborough/Wentworth Hall and Wortley Hall were occupied by the army. Wentworth Hall went on to become a teacher training college and later an adult education centre; Wortley Hall was bought by a Labour Co-operative to be used as an education and holiday centre, where the partly derelict hall and grounds were restored by a voluntary workforce (Wortley Hall 2001). Bretton Hall also became a teaching college in 1949, later becoming part of the University of Leeds; it is now set to become the site of a hotel and luxury spa (Wakefield Council 2007). The grounds were sold separately and became the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Some of the elite residences associated with smaller areas of parkland sustained their private use until a later date, presumably because of the smaller financial pressures involved in their upkeep. However, many of these became offices or were divided into a number of separate dwellings in the late 20th century.

Arable cultivation of parkland is noticeable at a number of the parks within the zone. Turning over parkland to arable production may be how the landowner managed to retain private ownership of the estate, but this trend has led to the loss of many park features.

The late 20th century trend to maintain park landscapes as heritage sites, because of their public amenity value, has led to restoration programmes of both house and park landscapes at several locations. Stainborough Park is currently undergoing such a programme and the surviving parts of Worsbrough Park have been developed as a country park (with the addition of former 19th century industrial sites around Worsbrough Basin).

Pressure from housing and commercial development has led to urban encroachment on some parkland landscapes. This has occurred at ‘Noblethorpe Hall’, ‘Birthwaite Hall’ and on the edges of ‘Cannon Hall’. This pressure has also led to the loss of other areas of 18th century parkland, within the urban centres of the district.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Birthwaite Hall (Map)

- Bretton Park (Map)

- Burnt Wood Hall (Map)

- Cannon Hall (Map)

- Haigh Hall (Map)

- Middlewood Park (Map)

- Noblethorpe Hall (Map)

- Stainborough Park (Map)

- Worsbrough Park (Map)

- Wortley New Park (Map)

- Wortley Old Park (Map)

Bibliography

- Jones, M.

- 2000 The Making of the South Yorkshire Landscape. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

- Moxon, C.A.

- 2000 Rowland Wilkinson's Cawthorne. In: B. Elliott (ed.), Aspects of Barnsley 6. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books, 151-170.

- Newman, R. Cranstone, D. and Howard-Davis, C.

- 2001 The Historical Archaeology of Britain c.1540-1900. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

- Rackham, O.

- 1986 The History of the Countryside. London: J.M.Dent.

- Wakefield Council

- 2007 Bretton Hall to be Transformed. Wakefield Council Press Release, 02/11/07 [online]. Available from: www.wakefield.gov.uk/News/PressReleases/news/pr1579.htm [accessed 28/02/08].

- Wentworth Castle and Stainborough Park Heritage Trust

- 2006 Wentworth Castle Gardens and Stainborough Park [online]. Available from: http://wentworthcastle.org/ [accessed 03/03/08].

- Wortley Hall

- 2001 Wortley Hall, Brief History [online]. Available from: www.wortleyhall.com/history.php [accessed 12/05/08].