Planned Industrial Settlements

Summary of Dominant Character

The dominant characteristics of this zone largely relate to rapid development between 1900 and 1939, to accommodate miners from pits on the concealed coalfield (Hill 2002, 16), which were sunk between the years 1905 and 1916 (Gill 2007). Post-1939 development within all of these character areas has been extensive and is discussed below as a part of the ‘Later Characteristics’ section.

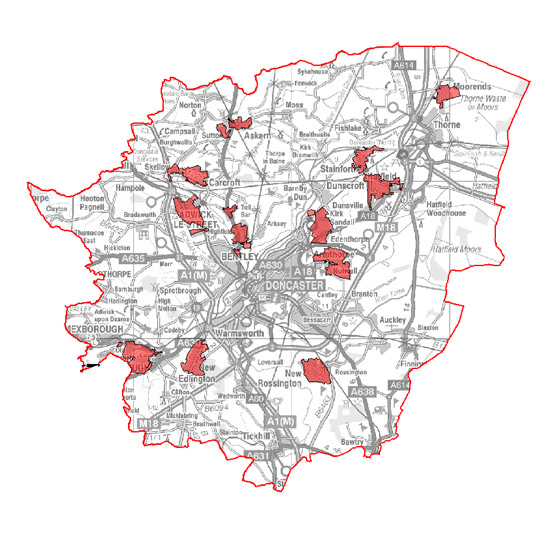

Figure 1: Location of character areas making up the ‘Planned Industrial Settlements’ zone.

Base mapping © Crown Copyright, All Rights Reserved. Licence no 100018816. 2007

The provision of the initial houses for the workers of these pits was generally the responsibility of single landlords, the resulting planned settlements being late examples of such guided development. Earlier examples would include the 42 or more dwellings built, converted or repaired for miners at Elsecar [Barnsley] between 1796 and 1798, or the estate villages that were developed by landowners as part of the beautification of their estates during the 18th and 19th centuries, of which Hickleton and Sprotbrough are good examples (Holland 1980, 42).

Although this zone principally includes settlements related to the housing of coal miners, the model village of Kirk Sandall, developed for workers of the adjacent glassworks (Skinner 1997, 172), has been included; it too has single company origins and similar planned characteristics. The industrial concerns in which these workers laboured were typified by the rapid development and expansion of privately owned companies, frequently employing between 1,000 and 3,500 men (Taylor 2001, 144-148). Pre-World War II development of these communities is generally marked by geometrically planned estates of brick built and pebble-dashed ‘cottages’ (sometimes semi-detached houses, but more usually short terraces of 4 or 6 houses). There are strong garden suburb influences, although at Bentley New Village, Carcroft, Denaby Main and New Edlington the earliest phases have more in common with patterns favoured in the ‘Grid Iron Terraced’ zone, due to their higher densities, less coherent overall plans and longer ranges of conjoined housing. New Edlington, in particular, remained something of an anachronism throughout the 20th century, never developing a coherent garden village plan. The village was criticised in Abercrombie and Johnson’s comprehensive 1922 Doncaster Regional Planning Scheme, which hailed Woodlands as “a model of what the new communities should be like” whilst deriding New Edlington as, “leav[ing] nearly everything to be desired in its planning and the way the work has been carried out” (Abercrombie and Johnson 1922 cited in Holland 1980, 66).

These differences largely reflect the age at which the settlements were developed. The Don Gorge, where the river Don cuts through the belt of Magnesian Limestone in the west of borough, provided an opportunity to access the concealed coal measures further east than would otherwise have been possible at that time, allowing the collieries of Denaby and Cadeby Mains (see the ‘Post Industrial’ character zone) to be established in 1859 and 1889 respectively. The new village of Denaby Main1 , which took its name from the colliery it served to differentiate it from the historic nucleated village to its west, took the same form as developments in the contemporary ‘Grid Iron Terraced’ suburbs. Housing was provided in blocks of conjoined terraced housing with shared open plan backyards in which were provided communal toilet blocks. This housing was developed in stages from the 1860s-early 1900s (Jones 1999, 127-129). The only surviving part of these brick built developments, on Wheatley Street, Tickhill Street and Tickhill Square, are not typical as they are larger in size. The earlier, much higher density development has since been demolished (see ‘Later Characteristics’), leaving no legible features.

Features commonly associated with this zone and influenced by the garden village movement, include:

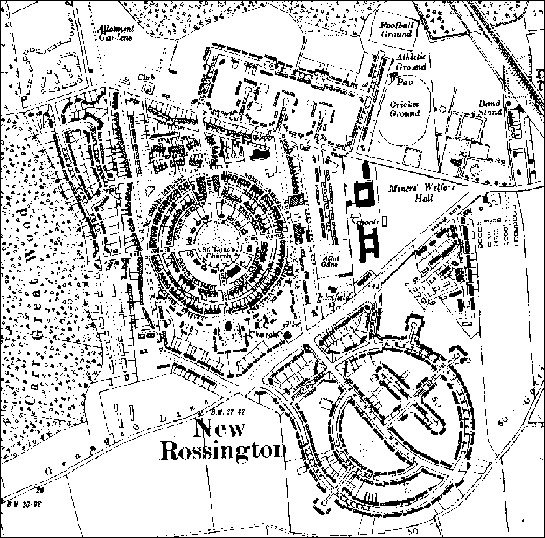

- Radial plans2 that frequently make use of concentric circles divided by axial roads (examples can be seen at New Rossington, Moorends, Woodlands, Armthorpe, and Conanby).

- Generous provision of garden plots.

- Architectural forms referencing supposed ideas of vernacular character and tradition, emulating idealised cottages. Styles favoured to achieve this effect were generally influenced by the ‘Arts and Crafts’ revival of the late 19th century and the ‘Neo-Georgian’ school of architecture (English Heritage 2007b).

- Communal open spaces surrounding cottages in the supposed tradition of English village greens3 (the best surviving examples are within the earliest estates at Woodlands, Kirk Sandall and Stainforth). A potentially unique modification of this characteristic was at Carcroft New Village where cottages were arranged around central allotment gardens. The most generous open spaces were at Woodlands, in the area designed by celebrated architect Percy Bond Houfton (Stratton 2000, 26).

Figure 2: New Rossington village shows most of the characteristic features of this zone.

1938 OS 6 inch to the mile mapping (not reproduced at scale) © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024

The mining villages also generally feature facilities originally provided by the Miners Welfare Fund, the product of a levy paid by colliery companies of 1d on every ton of coal produced, following the Mining Industry Act of 1920 (Griffin 1971, 170). At collieries this fund provided pit-head baths, but within this zone notable features provided are welfare halls, recreation grounds and parks – often co-located in welfare grounds. The provision has certain characteristics - team and spectator sports are well catered for, with football and cricket pitches at most grounds. Cricket grounds were often multi-functioning, with tracks provided around their boundaries for cycling and athletics at Woodlands, New Edlington and Moorends. Some grounds also include provision for tennis and bowling. Large areas of allotment gardens can also be seen on the 1930s OS maps of these settlements, although these have generally been neglected or have been overbuilt during the 20th century.

Clear organisational principles indicating the differentiation of status are apparent at most of these settlements, with small numbers of clearly larger houses provided, sometimes in prominent positions. At New Rossington a ring of larger houses are situated at the hub of the main plan, overlooking a central green, whilst most settlements feature one detached house in its own grounds - designated for the overall pit manager. The motivation behind such clearly visible and planned differentiation has been characterised by one writer as “a visible reminder of who wielded power in an early twentieth century mining community” (Holland 1980, 67).

Institutional buildings contemporary with the early planned villages reflect something of the dispersed origins of the immigrant communities attracted to them - by work in their mines and by their high standards of living. New Rossington’s planned layout included brick built Church of England, Roman Catholic and Methodist churches (Stratton 2000, 26).

Relationships to Adjacent Character Zones

The most obvious relationships between this zone and others is with the ‘Industrial’, ‘Extractive’ and ‘Post Industrial’ zones, where the sites of the commercial concerns that influenced these settlements are/were located. All of the character areas of this zone generally abut or are located close to historic villages, described by this project in the ‘Nucleated Rural Settlement’ zone. The wide variety of landscape types on which the collieries were sited (see ‘Extractive’ and ‘Post Industrial’ zone descriptions) means that the settlements of this zone are now sited amongst a range of enclosure types.

Inherited Character

The mines of this district often extended across large underground colliery ‘royalties’ [the areas of land from under which each company had rights of extraction] of up to 10,000 acres (Hill 1997, 16) - much larger than the areas worked to the west of the coalfield, where much closer spaced collieries each worked areas of up to 3,500 acres. These larger royalty areas were generally a response to the increased cost of sinking the much deeper pits necessary to penetrate the limestone and sandstone layers overlying the coals measures in the concealed coal field. This economically determined pattern resulted in the typical rural location of the settlements of this zone, “each village being separated from each other by large tracts of countryside” (Jones 1999, 124). This is in stark contrast to the older colliery settlements to the west, for example in the Dearne Valley, where settlements related to different collieries tend to merge into each other by the late 19th century.

Within this zone, evidence relating to the largely agricultural landscape on which the settlements developed is generally rare. Exceptions include the boundaries of various phases of development, which often coincide with historic enclosure boundaries, and earlier rural lanes that were incorporated into the later planned designs. More comprehensive legibility survives of an earlier formally designed landscape at Edenthorpe village. Edenthorpe Hall, only one wing of which now survives as part of Edenthorpe Hall Junior School, was built in the late 18th century and was originally surrounded by ornamental grounds. Within these grounds lay an older complex of 17th century manorial buildings that have survived in part as converted residential buildings at the end of Cedric Road. Magilton (1977, 38) records this area as the site of Streetthorpe or Stirestorp, a deserted medieval village.

Later Characteristics

Each of the character areas that make up this zone include areas of later private development. These later additions are normally found on the outer edges of character areas and have been included within this zone despite their later origin as they are still very much a part of the individual settlements. Coherent trends can be discerned in the changing patterns of development since World War II and the rest of this section will be described in two periods, 1939-1976 and 1976-2003.

1939-1976

On January 1st, 1947 a notice was posted at every colliery at the country reading,

“THIS COLLIERY IS NOW MANAGED BY THE NATIONAL COAL BOARD ON BEHALF OF THE PEOPLE”

(NCB notice reproduced in Hill 2001, 36).

At the time of nationalisation, all assets of the former colliery companies, including 140,000 houses nationally, passed to the new coal board (Beynon, Hollywood and Hudson 1999, 2). The NCB continued to take a role in the construction of housing estates to attract workers up to 1976, when it withdrew from the provision of miners housing (ibid, 3). Housing was generally built as part of large-scale public sector social housing schemes [characterised at character unit level in this project as ‘Planned Estate (Social Housing)’]. Until the 1970s, development led by the private sector was generally small-scale, and mostly consisted of ribbon development along main roads. The earliest housing constructed during this period has superficial characteristics in common with the model villages - estates dating to the 1950s were often built in geometric plans and semi-detached and ‘short-terrace’ housing was dominant. However, open spaces became less common and the housing density tended to increase.

From the mid 1950s onwards there was a clear move away from the provision of private space to open plan estates based on the ‘Radburn’ principles of design. These principles, originating in a study by US architects Stein and Wright of English ‘garden suburb’ planning (Sheffield Corporation 1962, 12), aimed to maximise the separation of vehicles and pedestrians by avoiding points at which pedestrians would have to cross vehicle carriageways. Instead of facing on to carriageways, houses were designed to front directly onto common green spaces, without privately demarcated enclosed gardens. The ‘Radburn’ estates built in this zone in this period are typical of many developed nationwide from the 1950s through to the late 1970s and are generally constructed according to ‘system building’ techniques, typically the ‘No Fines’ method developed by Wimpey. Houses built in this way were cast in-situ from a concrete mix requiring no ‘fine’ aggregates (i.e. cement and gravel). This method could be executed quickly and cheaply – however, the resulting aesthetics of the properties, which were finished with quickly applied render, are generally regarded as bleak. Structural problems with the system include poor thermal insulation and condensation.

Figure 3: ‘Radburn’ style estate planning (seen here at New Edlington) sought to maximise separation of vehicles and pedestrians.

Image © 1999 Cities Revealed / The Geoinformation Group.

1976 - 2003

Developments in these settlements during this later period are strongly divided along economic lines. New development was dominated almost entirely by the construction of privately funded owner-occupied housing. Large estates of detached cul-de-sac and bungalow housing were added to the older villages at Adwick le Street, Armthorpe and Conisbrough.

The areas of social housing described above have, in some cases, undergone a widespread decline. Much debate has focused on the changes in government policy towards the nationalised coal industry and social housing during the 1980s and 1990s, a period in which all but two of the pits that supported settlements in this zone were closed for good. Much of the working population here was directly involved in a violent and economically devastating industrial dispute (Adeney and Lloyd 1986), and large volumes of council and NCB owned social housing were transferred to the private sector. The sale of NCB housing in particular, undertaken in a very short period between 1985-8, has been blamed for a physical and social decline, much of the property being purchased by absentee landlords for very low prices (Beynon, Hollywood and Hudson 1999,3).

Urban design theories (Doncaster MBC undated d, 18) have turned away from the open plan concept of the ‘Radburn’ estates, which is now believed to offer no ‘defensible space’, to increase the security and privacy of residents. The common parking areas provided to the rear of ‘Radburn’ property have been criticised as “poorly overlooked and magnets for anti-social behaviour” (CSR Partnership 2004, 26). South Yorkshire’s ‘Housing Market Renewal’ programme has made the ‘de-Radburnisation’ of some of these settlements a specific target, particularly at Denaby Main, where the grid iron terraced properties described above were demolished and replaced with ‘Radburn’ estates in the 1960s and 70s (Jones 1999; Chan 2007).

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Armthorpe Colliery Village (Map)

- Askern Village (Map)

- Bentley New Village and Toll Bar (Map)

- Carcroft and Skellow Villages (Map)

- Conanby / Denaby Main Villages (Map)

- Hatfield Colliery Village (Map)

- Kirk Sandall and Edenthorpe Planned Settlement (Map)

- New Edlington Village (Map)

- New Rossington Village (Map)

- Stainforth Colliery Village (Map)

- Thorne Moorends (Map)

- Woodlands Highhfields and 'new' Adwick le Street (Map)

Bibliography

- Adeney, M. and Lloyd, J.

- 1985 The Miners Strike 1984-5: Loss Without Limit. London: Routledge.

- Beynon, H., Hollywood, E., and Hudson, R.

- 1992 Regenerating Housing: Coalfields Research Programme, Discussion Paper 6 [online]. Cardiff: Cardiff University. Available from: http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/socsi/resources/regenerating%20housing%20-%206.pdf [07/08/2008].

- Chan, S.

- 2007 Doncaster Housing Market Renewal (HMR) Pathfinder Programme – Masterplans for Woodlands Way Neighbourhood, Denaby Main and Associated Programme [online]. Report of Housing Strategic Initiatives Manager to Mayor and Members of Cabinet, Doncaster MBC Available from: http://www.doncaster.gov.uk/about/chamber/.%5CReports%5C031007Cabr4.doc [05/01/2008].

- CSR Partnership

- 2004 Masterplanning at Royal: Granby: Howbeck Estates, Edlington [online].CSR Partnership for Doncaster MBC / Transform South Yorkshire Available from: http://www.doncaster-community.co.uk/Living_in_Doncaster/Homes_and_Housing/HMR_pathfinder/edlington/Masterplans_for_Edlington.asp [07/08/2008].

- Doncaster MBC

- [undated] Landscape Planning on Development Sites in Doncaster: Consultation Draft, Doncaster, Doncaster MBC Environment and Planning Services.

- English Heritage

- 2007a The Heritage of Historic Suburbs [online]. London: English Heritage. Available from: http://www.helm.org.uk/upload/pdf/Heritage-Suburbs.pdf [07/08/2008].

- English Heritage

- 2007b The Modern House and Housing: Selection Guide – Domestic Buildings (4) [online]. London: English Heritage, Heritage Protection Dept. Available from: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/upload/pdf/Domestic_4_Modern_House_and_Housing.pdf [07/08/2008].

- Griffin, A.R.

- 1971 Mining in the East Midlands 1550-1947. London: Frank Cass and Co.

- Hill, A.

- 2002 The South Yorkshire Coalfield: A History and Development. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

- Holland, D.

- 1980 Changing Landscapes in South Yorkshire. Doncaster: D. Holland

- Howard, E.

- 1902 Garden Cities of Tomorrow. London

- Jones, M.

- 1999 Denaby Main: The Development of a South Yorkshire Mining Village. In: B. Elliot (ed.), Aspects of Doncaster 2: Discovering Local History. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books, 123-142.

- Magilton, J.R.

- 1977 The Doncaster District: An Archaeological Survey. Doncaster: Doncaster Museum and Arts Service

- Gill, M.

- 2007 Mines of Coal and other Stratified Minerals in Yorkshire from 1854 [Geo-referenced Digital Database]. Available from: Northern Mines Research Society

- Sheffield Corporation

- 1962 Ten Years of Housing in Sheffield. Sheffield: Sheffield Corporation: Housing Development Committee

- Skinner, J.S.

- 1997 Form and Fancy: Factories and Factory Buildings by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners, 1916-1939. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press

- Stratton, M.

- 2000 Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Taylor, W.

- 2001 South Yorkshire Pits. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

- Unwin, R.

- 1994 Town Planning in Practice: An Introduction to the Art of Designing Cities and Suburbs [originally published 1909]. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Waithe, M.

- 2006 William Morris's Utopia of Strangers: Victorian Medievalism and the Ideal of Hospitality. Woodbridge: D.S.Brewer.

1 ‘Main’ was appended as a suffix to colliery names in South Yorkshire to indicate those that were exploiting the thickest coal seam ‘Main’ or ‘Barnsley Bed Seam’ (Hill 2001, 7).

2 Radial ‘spiders web’ plans were championed in Howard’s original ‘Garden City’ proposals (1902, 50-57) and in Raymond Unwin’s development of the concept (Unwin 1994 [1909], 236)

3 Unwin believed that this arrangement would help engender community relations between the occupants of the cottages (Waithe 2006, 188)