Post Industrial

Summary of Dominant Character

This zone is characterised by late 20th century landscapes of retail, distribution, leisure, light industry and transport. The zone has developed across a variety of former landscapes from the later 20th century onwards. Landscapes associated with former collieries in this zone tend to consist of large areas of recently landscaped parkland, plantation woodland, or unmanaged regenerative scrubland and are sometimes associated with commercial, light industrial or distribution estates. An example is Brodsworth Main, where spoil heaps from the colliery (closed in 1990 (Hill 2001, 195)) have been landscaped as a community woodland since 1997 (Land Restoration Trust 2004).

Character areas within this zone are large in scale, within the range of 100 – 250 hectares. At some sites, land is used explicitly for amenity purposes, for example in the ‘Denaby and Conisborough post-industrial area’. Here the sites of Cadeby Main Colliery, Denaby Main Colliery and other industries have left a large area of post-extractive land, designated in the late 1990s for reuse as a wildlife sanctuary and environmental education centre. During the life of the characterisation project these areas consisted of large landscaped slurry lakes and spoil tips augmented with immature plantation woodlands and ornamental gardens, in addition to the post modern architectural forms of the Earth Centre visitor centre (a millennium project). Closely related is the site of the disused Thorpe Marsh coal-fired power station, which, despite the loss of most of its buildings including its enormous generating hall, retains a group of six cooling towers that dominate the surrounding flat landscape for miles around. The former coal storage area to the west of the site is now a part of Thorpe Marsh Nature reserve.

The landscapes to be found in the non-extractive character areas of this zone range from those directly concerned with modern transport infrastructure, notably the major intersections of the A1 and M18 motorways, and RAF Finningley, which re-opened in 2004 as Robin Hood Doncaster Sheffield Airport (Carter 2004). The road junctions are built in stark poured concrete characteristic of much of the UK motorway network, and are generally ‘grade separated junctions’, where earthwork embankments and cuttings provide sloping slip-roads that join the main carriageways to the rest of the trunk road system, often via large elevated roundabouts. The oldest parts date to the early 1960s, when the A1 was upgraded to a dual carriageway and the Doncaster Bypass was built. In 1967 a short section of the M18 was built between Wadworth and Thurcroft (within Rotherham) linking the A1 to the M1; work to extend the road to the M62 progressed in stages throughout the 1970s. A further spur towards North East Lincolnshire (the M180) was opened in 1977 (dates from Hewitt, 2007).

The intersection of these roads has encouraged the growth of large distribution centres for the retail industry. A typical example of the type of landscape related to this influence is the ‘West Moor Park’ character area, developed on formerly agricultural land adjacent to Junction 4 of the M18 between 2000 and 2008. West Moor Park includes distribution and retail centres for major UK retailers, housed in massive prefabricated sheds surrounded by large areas of tarmac used for car parking and distribution vehicles. Typically these buildings have few windows but many bays of doors into which large articulated road haulage vehicles can be reversed for loading and unloading. Similar development patterns can be observed at Redhouse Park, adjacent to J31 of the A1(M), and the Thorne Commercial Parks, developing between J6, the M18 and the town of Thorne.

The remaining strand of development characterising this zone is the provision of areas of large-scale commercial leisure provision, most noticeable at the ‘White Rose Way and Lakeside’ character area. This area of mixed commercial, industrial and ornamental character has been largely developed since the mid 1980s, to take advantage of the White Rose Way dual carriageway. This was built across the former Doncaster and Potteric Carrs between 1979 and 1984, to link the centre of Doncaster with the M18 to the south. Developments here include the Doncaster Dome leisure centre and arena complex [1985-1989]; Lakeside Village retail park, call centres and offices [1996]; and the 15,000 seater Keepmoat Stadium [2006] (Doncaster MBC 2007). These developments, all of which feature large areas of car parking, are set around a near circular artificial lake and are linked by further parkway dual carriageways, Lakeside Boulevard and Gliwice Way, which map evidence shows were built between 1984 and 1999.

Relationships with Adjacent Character Zones

This zone is widely distributed across the Doncaster borough and there is no clear relationship with any other zone. However, the majority of this zone developed across previously extractive landscapes, providing a chronological relationship with the ‘Extractive’ zone. These former colliery sites also all relate to adjacent ‘Planned Industrial Settlements’.

Inherited Character

The South Yorkshire coal reserves consist of both an exposed coalfield, where seams outcrop at the surface and are consequently more accessible, and a concealed coalfield, where the carboniferous strata (in South Yorkshire the Coal Measures Sandstones) are overlain by later geological deposits of Permian and Triassic limestone and sandstone. The shallower depth of the most productive seams in the exposed coalfield (most notably the ‘Main’ or ‘Barnsley Bed’ seam, from which many collieries gained part of their name) meant that mining was concentrated to the west of South Yorkshire until the late 19th century (Hill 2002, 16). However, by the end of the 19th century collieries to the west of the coalfield were beginning to become exhausted and advances in technologies of transport, ventilation and pumping were beginning to make the exploitation of the deeper concealed coalfield a reality.

Most of the Doncaster sites within this zone were first sunk between 1903 and 1916, with the exception of Cadeby and Denaby Mains (within the ‘Denaby and Conisborough Post-Industrial’ character area), which exploited natural cuttings through the Magnesian Limestone made by the Don Gorge. These two pits were first sunk in 1889 and 1856 respectively (Gill 2007). Denaby was worked until 1968 (all coal winding having transferred to Cadeby in 1956) and Cadeby closed in 1986 (Hill 2002, 156-7). By 1999 aerial photography showed both pit heads as levelled sites, with tracks removed from the extensive rail sidings serving both sites. Landscaping for post-industrial leisure uses has since affected both sites – the extensive spoil heaps to the north east of Cadeby becoming part of the ill-fated Earth Centre development [1999-2005 (Dunlop 2005)]; the pithead site at Denaby Main has been overbuilt by the Dearne Valley Leisure Centre, opened in 2002. Legibility of the former collieries is now restricted to the landscaped spoil heap and the pedestrian bridge to the Earth Centre across the Don.

The remaining former colliery sites within this zone were not exploited by the coal industry until the 20th century, the earliest sinking being at Bentley Main in 1903 and the most recent at Askern in 1911 (Gill 2007). The shortest lived of these pits was Bullcroft Main (1908-1970), closed after an underground tunnel was dug towards workings of Brodsworth Main, allowing the Bullcroft coal to be wound there (Hill 2001, 210). The next to close was Yorkshire Main in 1985 (ibid). Unsurprisingly the collieries that have been closed the longest have the most established post-extractive uses, with substantial industrial estates now operating at both Bullcroft Main and Yorkshire Main.

The remaining collieries in this zone closed in the period 1990-1996, a major period of contraction of the industry nationally. This contraction has been attributed (for example, by Hill 2001, 51) to the use of cheaper imported coal at the time of electricity privatisation from 1990 onwards. At the time of this project these sites were good examples of ‘interstitial landscapes’ (Bradley et al 2004) – landscapes that existed at a point of time between two clear uses but without clearly defined current status. Aerial photographs of these sites taken in 1999 (Geoinformation Group 1999) clearly show this state at these sites – pit head buildings have been cleared down to concrete slab levels with surrounding former siding yards and spoil heaps generally left to regenerate as scrub.

At none of these former colliery sites has any legibility of earlier rural landscapes survived the development of the coal mines, although the boundaries of sites are likely to follow older patterns of land enclosure.

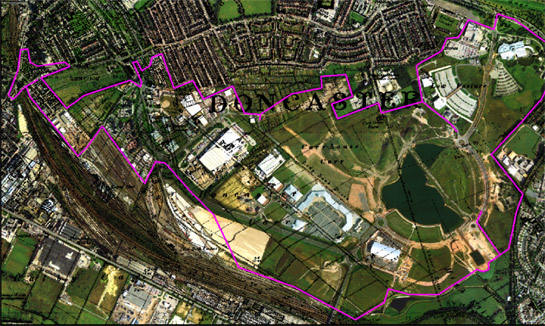

Patterns of legibility and development are more complex within the non-extractive character areas of the zone, although even here there are examples where the former agricultural or industrial landscapes are not legible following (re)development. The commercial and leisure developments at the ‘White Rose Way and Lakeside’ area, between suburban Doncaster and the Hexthorpe railway yard, has nearly completely erased traces of earlier character. Comparison of the modern landscape with that of the early 20th century shows the extent to which the landscape has been reconfigured.

Figure 1: The ‘White Rose and Lakeside’ character. Legibility of the former landscape (the 1938 6 inch to the mile OS is overlain in black) has been completely erased by mid 20th century tipping and by ongoing construction of the commercial landscape of Lakeside and Doncaster Dome.

Cities Revealed aerial photography © the GeoInformation Group, 2002; © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024

There is more legibility of the former RAF Finningley, despite its second life as Robin Hood Doncaster Sheffield Airport. The RAF base was opened in 1936 as part of the RAF’s ‘expansion period’1 building programme initiated as a counterpoint to German re-armament. Expansion during World War II saw more runways added. In the mid 1950s the runway was further upgraded to accommodate Vulcan bombers, then the delivery system for the British Nuclear capability. Nuclear weapons storage facilities were also added at this time. The base became a training facility from the 1970s onwards, until closing as a military base in 1996 (Scott Wilson Kirkpatrick 2002, 13C/5-13C/6). Despite redevelopment as a civil airfield, the site has retained much of the original fabric of the base intact, including the World War II hangars, although cold war period nuclear weapons stores have been destroyed (R. Sykes pers. com). Construction of the airfield in the 1930s removed all legibility of earlier rural landscapes within the perimeter fence.

Later Characteristics

This zone is one of the most recent developments to affect the Doncaster landscape. It is, therefore, best to consider it as a growing zone, likely to expand over the next decade, especially across rural and post-extractive land adjacent to the A1 and M18 junctions, as well as around existing industrial and commercial areas. During the life of the characterisation project work has been in progress at most of the former colliery sites of this zone, most notably in the establishment of community woodlands and nature reserves.

Not all regeneration in this zone has been a resounding commercial success. The closure of the Earth Centre after only 5 years due to lack of visitor numbers being a case in point (Dunlop 2005).

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

Former Collieries and Power Station

- Askern Main Site / Askern Mather (Map)

- Site of Bentley Colliery (Map)

- Site of Bullcroft Main (Map)

- Brodsworth Main and Redhouse (Map)

- Denaby and Conisborough post-industrial area (Map)

- Markham Main (Armthorpe) Colliery Site (Map)

- Thorpe Marsh Power Station Site (Map)

- Site of Yorkshire Main Colliery (New Edlington) (Map)

Other Sites

- A1, M18 & M180 Intersections and Junctions (Map)

- Bankwood Industrial Estate (Map)

- Former Pilkington Glassworks site, Kirk Sandall (Map)

- Mexborough Late 20th century Commercial Area (Map)

- North Bridge Post Industrial area (Map)

- Robin Hood Airport (Map)

- Shaw Lane Industrial Estate (Map)

- Thorne Commercial Parks (Map)

- West Moor Park (Map)

- White Rose Way and Lakeside (Map)

Bibliography

- Bradley, A., Buchli, V., Fairclough, G., Hicks, D., Miller, J. and Schofield, J.

- 2004 Change and Creation: historic landscape character 1950-2000. London: English Heritage.

- Carter, H.

- 2004 Nottingham not so merry about Robin Hood airport. Guardian Unlimited [online], 14th April, 2004 – UK News. Available from: www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,1191318,00.html [accessed 14th January, 2004].

- Doncaster MBC

- 2007 Doncaster Lakeside [online]. Available from: www.doncaster.gov.uk/Working_in_Doncaster/Invest_in_Doncaster/site_and_premises/Doncaster_Lakeside.asp [accessed 15/01/07].

- Dobinson, C.S.

- 2000 Twentieth Century Fortifications in England: Volume IX, Airfield Themes. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Dunlop, E.

- 2005 Earth Centre closed for good as rescue bid fails. Yorkshire Post [online], 14th April, 2005. Available from: www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/Earth-Centre-closed-for-good.997707.jp [accessed 16/01/08]

- Gill, M.

- 2007 Mines of Coal and other Stratified Minerals in Yorkshire from 1854 [Geo-referenced Digital Database]. Available from: Northern Mines Research Society, 38 Main Street, Sutton in Craven, KEIGHLEY, Yorkshire, BD20 7HD.

- Geoinformation Group

- 1999 Cities Revealed: Doncaster [geo-rectified aerial photography supplied on cd-rom]. Fulbourn: Geoinformation Group.

- Hewitt, P.

- n.d The Motorway Archive [searchable online database]. Available from: www.ukmotorwayarchive.org/ [accessed 14/01/08].

- Hill, A.

- 2002 The South Yorkshire Coalfield: a History and Development. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

- Land Restoration Trust

- 2004 Sites: Brodsworth South Yorkshire [online]. Warrington: Land Restoration Trust. Available from: www.landrestorationtrust.org.uk/sites_Detail.asp?si=44&l1=4 [accessed 14/01/08].

- Scott Wilson Kirkpatrick Ltd

- 2002 Doncaster Finningley Airport, The Airport Proposals. Environmental Statement: Final Report Volume 2: Appendices [Unpublished]. Leeds: Scott Wilson Kirkpatrick and Co Ltd.

1 The RAF’s ‘expansion period’ dates to 1934-1939 and the Expansion Schemes A-M, which sought to rapidly expand UK air capabilities following the withdrawal of Germany from the League of Nations Disarmament Conference in Geneva (Dobinson 2000, 73-119)