Suburbanised Rural Settlements

Introduction

The character areas described within this zone are suburban areas where the growth of settlement character relates not to the historic core of the medieval market town of Sheffield, but to historic core areas and industrial activity in other locations. There is substantial variation in the character of this zone, both from one character area to another (dependent on their local geological and industrial heritage) as well as within each character area (which are typically made up of a number of phases of expansion around historic core areas). These variations will be described here in sub-zones, where there are fundamental similarities across the character areas.

The Industrial Towns

Summary of Dominant Character

Figure 1: The oldest part of Stocksbridge works - Samuel Fox’s wire mill - with part of the industrial town in the background

© 2007 Dave Bevis – licensed for reuse under this creative commons license.

The historic attributes of this sub-zone are fundamentally linked in each case to the growth of the heavy industries that provided the initial stimulus for their foundation (in the case of High Green, Mortomley and Stocksbridge) or their rapid mid 19th century to early 20th century growth (in the case of the earlier medieval core settlements of Tinsley and Chapeltown). The heavy metal industries were the basis for the growth of each settlement. High Green, Mortomley, Chapeltown and Charlton Brook all grew in relation to the large ironworks and the related industry of the processing of coal tar, dominated by the local firm of Newton Chambers and Co (see Elliot c1958). Stocksbridge grew in relation to the works of Samuel Fox and Co., whose works began as a production site for drawn wire before diversifying into bulk production and processing of steel in the later 19th and through the 20th century. At Tinsley, the first phases of suburban development can be related to the contemporary growth of the major steel works of Hadfields (East Hecla Works) and Steel, Peech and Tozer (Templeborough Works), whilst later expansion is contemporary with the growth of the Firth Vickers (later British Steel, Corus, Avesta and Outokumpo) site at Shepcote Lane.

Historic buildings predating the mid 19th century are generally rare in this zone, with the earliest urban landscapes generally made up of terraced workers housing and related institutional buildings. In Stocksbridge, Chapeltown and High Green these developments are generally stone rather than brick fronted, although brick is a more common material after the late 19th century. The terraced housing in Tinsley is generally of early 20th century date and usually of brick construction.

Some level of early 20th century ‘model’ housing is evident, particularly in the small cottage estates of Mortomley and at Garden Village, Stocksbridge. These developments are comparable to larger scale examples of ‘model villages’ built by local mining companies, such as the planned community of Woodlands near Adwick-le-Street in Doncaster, consisting of idealised ‘cottages’ on geometric street patterns influenced by the ‘garden village’ movement and typically associated with simple landscaped sporting facilities such as recreation grounds, parks and bowling greens.

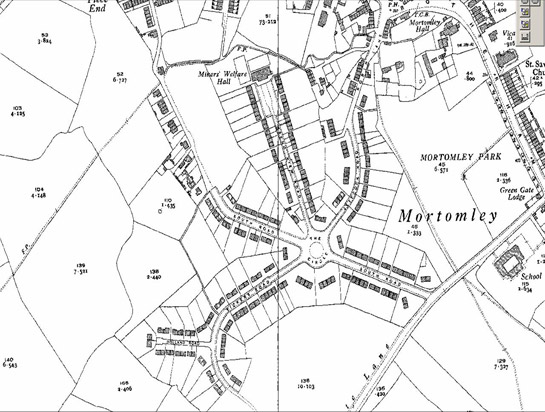

Figure 2: Mortomley village is similar in plan form to the garden villages in the Rotherham, Barnsley and Doncaster ‘Planned Industrial Settlement’ Zones

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

The development at Mortomley includes a prominent and listed Miners Welfare Hall. Not far from the Mortomley Estate, at Mortomley Close, stand 8 semi-detached houses built using a system based on prefabricated cast iron components developed after World War I by the castings department of Newton Chambers, to use spare foundry capacity left redundant by the drop in orders for shell casings (Jones and Jones 1993).

Inherited Character

Whist both Chapeltown and Tinsley have medieval origins and are depicted on 1850s OS mapping as small nucleated villages associated with open field systems, little survives of a pre-industrial character in either settlement. Vernacular buildings in Tinsley appear to have been largely cleared and replaced with late twentieth century municipal housing (probably related to 1960s clearance of supposed ‘slum’ housing). In Chapeltown the core of the historic centre was probably the triangular area near Market Street in which the 19th century Waggon and Horses now stands. The historic pattern of this nucleated settlement has been fundamentally compromised by the railway built through it towards the end of the 19th century.

Clearer surviving traces of the hamlets of Charlton Brook Hollowgate, Mortomley and High Green can be located. A number of vernacular buildings survive from these hamlets, as depicted in 1854 by the OS, including a 17th century building at Charlton Brook. High Green appears to have been enclosed by parliamentary award. Such newly enclosed land appears to have formed the earliest land developed as the hamlets began to grow into industrial villages and then towns.

Whilst no historic village of Stocksbridge seems to have existed, (the name relates to an earlier bridge across the Don at the site of the oldest part of Stocksbridge Works), the later development of the industrial town has preserved some fragments of the earlier dispersed settlements (within piecemeal enclosure) that it displaced. Most notable amongst these is the small hamlet of Pot House, which includes the scheduled remains of Bolsterstone Glass Furnace.

Later Developments

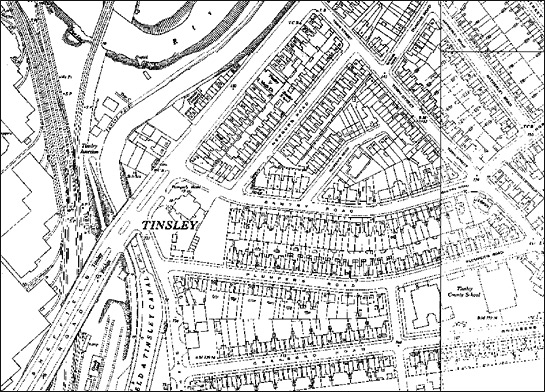

The earliest industrial terraces of Tinsley, dating to the late 19th century, were dramatically truncated by the construction in 1968 of the massive Tinsley Viaduct (see the ‘Post Industrial’ zone).

Figure 3: Above – 1950s mapping shows an area of terraced housing on the site of the later Tinsley Viaduct. Below – this 1967 aerial shot of the same area shows the severance caused by the massive southern roundabout for the viaduct.

Historic mapping © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024. Aerial photograph © 1967 Rotherham MBC

In Stocksbridge and Chapeltown / High Green later expansion of these settlements has been less distinctive than the earlier phases of housing, with later municipal housing of less quality and individuality than the earlier. These settlements have seen the construction of substantial areas of late twentieth century detached housing, mostly built in cul-de-sac estates with similarities to the housing built in the late 20th century at the Mosborough Townships. High Green features a large, mostly low rise estate around Cottam Road with some character similarities with the ‘Late 20th Century Private Suburbs’ zone.

Industrial Towns character areas

Map links will open in a new window.

The Colliery Villages

Summary of Dominant Character

This sub-zone occupies much of the south east of Sheffield, between the late twentieth century ‘Mosborough Townships’ and the municipal estates of Manor and Gleadless. The suburbanisation of this area has steadily increased from the mid 19th century onwards, in part due to the steady growth of coal mining here until the mid 20th century (when most of the area’s mines began to reach economic exhaustion) and, subsequently, due to the steady expansion of Sheffield’s urban area.

The sub-zone’s character is largely one of settlement, with the majority of the current landscape made up of residential units and related institutional and ornamental land-uses. The zone includes the remains of earlier nucleated villages at Handsworth, Woodhouse, Mosborough, Beighton, Gleadless, and Hackenthorpe, in addition to some smaller dispersed hamlets around the fringes of the historic Birley Moor. However, the majority of housing in the area dates to the early to mid 20th century, with large estates of semi-detached housing dating to the 1930s, built both privately and for Sheffield Corporation.

Coal mining in this zone appears to have declined in importance through the 20th century, with extraction ceasing at Beighton and Birley in the 1930s and 40s and at Handsworth in 1967. However, suburban development continued to be the dominant theme, with much infilling of open space between 1945 and 1975. Much of this development follows the trends established in the ‘Early to Mid 20th century municipal estates’ zone, with layout patterns generally consisting of medium density plots arranged in geometric forms.

Inherited Character

Field boundary and settlement patterns shown on 19th century historic maps of these areas are typical of open field agriculture. On the lower ground are semi-regular strip field patterns associated with nucleated villages, whilst the higher ground is dominated by substantial areas of common grazing land including Gleadless Common, Hollins End Common, Woodthorpe Common and Birley Moor. It is likely that these commons were enclosed as part of the Beighton and Handsworth Enclosure Awards of 1799 and 1805 respectively (dates from English 1985, 63; Kain and Oliver 2004, record EXMID 16913). Fragmentary historic features survive from this enclosure landscape, particularly the road system and some older post enclosure stone built buildings.

At Handsworth, despite substantial demolition at the end of the 19th century (and much rebuilding in terraced forms) and again later in the 20th century (as part of a scheme to turn Handsworth Road into a dual carriageway), a significant cluster of historic buildings survive around the 12th century parish church. These include two pre 18th century buildings that have incorporated parts of earlier timber structures.

Figure 4: Former Rectory, Handsworth – built in the late 17th or early 18th century, but containing part of a cruck timber

© SCC 1974

Elements of a street pattern with medieval origins can be traced in Woodhouse, centred on the historic Market Square and the surrounding streets of Church Street, Market Street, Chapel Street and Tannery Street. Around these streets a number of buildings predating the industrial period can be found, although again 20th century road and housing redevelopments have compromised the integrity of the historic core. Historic maps predating the suburbanisation of Woodhouse show a network of enclosed strips, clearly taken from earlier open fields. In the modern landscape only a small but important area of these characteristic curving boundaries survive as enclosed land, associated with a relict section of Water Slacks Lane. Elsewhere this pattern has been lost beneath industrial and residential development or has been removed by 20th century intensive cultivation methods.

The historic village of Mosborough (described in this zone separately from the surrounding ‘Mosborough Townships’, which form the ‘Late 20th century private suburbs’ zone) is first recorded in 1002 (Stroud 1996, 43). The original settlement appears to have been based around a curving main street leading from the medieval manor of Mosborough Hall, along the present Duke Street to South Street; historic narrow tenement plots are significantly legible along South Street. The present buildings in this area date mostly to the mid to late 20th century, but there are a number of important 18th century survivals including the listed no 31 and 32 (Summer House) South Street and the winnowing barns at Eckington Hall Farm, as well as the non listed 18th and 19th centuries buildings at The Pingle, Elmwood Farm (no 27 South St), no 37, The Alma Public House and the terrace of buildings to the north of Eckington Hall Farm. To the north of this area of probable medieval settlement, pre-enclosure survey information names Mosborough Green (see Stroud 1996, fig 19). The enclosure of this former common formed the basis of the current pattern of property divisions here. Street character in this later area of the village is uniform and regular in comparison to the older settlement area.

An area of historic settlement similar in character to those at Handsworth, Mosborough and Woodhouse can be discerned at High Street, Beighton. The pattern of boundaries in this area conforms to the typical layout of medieval nucleated settlements in South Yorkshire, with thin property boundaries perpendicular to a main street. Close by this area lies the church of St Mary the Virgin, which contains 14th and 15th century architecture in its tower and nave arcades despite a widespread 19th century restoration (Richards 1991). To the south of the main area of settlement, the 17th century manor farm is also preserved through residential re-use. Like Handsworth and Woodhouse, Beighton was historically related to a substantial open field system, progressively overbuilt to house a mining community from the early 20th century onwards. The earliest streets of this suburbanisation (Queens Road, Manvers Road and Victoria Road) were clearly built within earlier enclosed strip fields.

Later Developments

The post Second World War period brought major changes to the established patterns of suburbanisation. Whilst large cottage estate type developments continued, on some municipal developments a radical change of design direction was adopted by Sheffield Corporation (see Sheffield City Council 1962) in order to meet the considerable challenges and opportunities of increasing car ownership and large scale housing shortages. New housing projects built by the corporation from the late 1950s onwards generally rejected traditional building methods and architectural forms in favour of flat roofed blocks of multiple occupancy flats in estates featuring large communal green spaces where pedestrian and vehicular space was strictly segregated. The principal area for this type of development in this sub-zone was in Woodhouse, where large estates of system built houses were constructed between 1962 and the early 1980s. Elsewhere large amounts of older housing in the settlements’ historic cores were cleared in the 1970s, as part of a long standing programme to remove ‘unsanitary’ housing. This provided further opportunities for council led rebuilding. Later 20th and early 20th century private housing in this zone has tended to match the spatial characteristics of the suburban housing developments described in the ‘Late 20th Century Private Suburbs’ character zone.

Colliery Villages character areas

Map links will open in a new window.

The Enlarged Villages

Summary of Dominant Character

This sub-zone of the suburbanised rural settlements represents a group of historically nucleated settlements that have grown larger over the 19th and 20th centuries in a symbiotic relationship with the City of Sheffield. Most of these character areas have significant historic legibility. The historic cores of Dore, Totley and Ecclesfield display classic boundary patterns found in many medieval villages in South Yorkshire, with a clear pattern of one or more main streets off which run narrow plots of semi regular form, with later development clustered around them. Grenoside, Oughtibridge and Worrall were also certainly nucleated before the 1850s, although the pattern of properties in each was much less regular. At Stannington, historic settlement appears to have been of a more dispersed character, with the 1850 OS mapping showing a number of very loosely clustered farmsteads.

Suburban expansion of these settlements is highly mixed. Most have accommodated areas of terraced housing, municipal council housing of early and later twentieth century date, as well as private speculatively developed housing.

Inherited Character

Historically, the largest and most important of these settlements was Ecclesfield. It is likely to have been the ecclesiastical centre of a pre-Norman unit of Hallamshire, with historical documents claiming Sheffield as well as Bradfield as dependent chapelries as late as 1188 (Hey 1979, 28). The layout of the village, as depicted in the mid 19th century, has largely persisted in the present townscape, with regular plots along Town End Road, High Street and Church Street clearly corresponding to those shown on the first edition Ordnance Survey mapping. Within these plots some important stone built vernacular architecture survives, not least the scheduled 19th century former file factory at 11 High Street.

The ecclesiastical importance of the village is represented in the townscape by the fine medieval church of St Mary’s, at its centre. This church, at which evidence for a pre-conquest foundation was found in 1892 with the discovery of a Saxon cross shaft, includes Early English (c.1180 –c.1275) and Perpendicular (c.1350-c.1580) architecture (Pevsner and Radcliffe 1967, 185). Behind the church, lie the remains of a Benedictine Priory; the surviving buildings, restored in the 1880s, consist of two ranges, the first housing a chapel and the second interpreted as a refectory and dormitory block. The complex, particularly the chapel range, retains significant 13th century architectural elements (Ryder 1980, 453-454).

Figure 5: Ecclesfield file works

© 2005 SYAS

More fragmentary legibility of the medieval landscape continues to the north east. The present vicarage is a modern building, but it stands within the remains of a large 19th century garden. At the far end of this plot lies the scheduled Willow Garth, a probable medieval moated site. Beyond the moat lies a large dam, now used as a fishing pond, but formerly associated with a water powered mill – possibly on the site of the medieval corn mill of the priory (Miller 1949, 95).

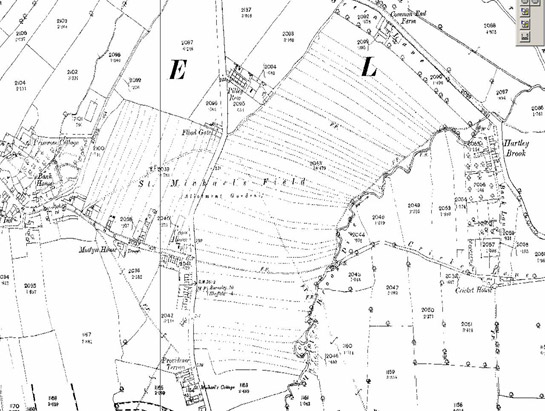

19th century OS mapping shows the historic core of Ecclesfield to have been surrounded by a distinctive network of narrow strip fields to the south and west, with common land to the north. Much of the former open field known as St Michael’s Field (to the east of the historic core area) remained unenclosed until the early 20th century – the original communal character being retained by the strips’ conversion to allotment plots. Those plots not retained as allotments were generally developed as housing between World War I and World War II – fossilising significant legibility of the earlier strip patterns.

Figure 6: 1894 OS mapping of the unfenced strips of St Michael’s Field in Ecclesfield. One of the latest examples of open common field patterns in Soutn Yorkshire.

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

Ecclesfield Common was enclosed by Parliamentary Award in 1789 (English 1985, 45). Much of the length of Church Street, The Common, Mill Road and the relict boundaries within Ecclesfield Park survive from this award. Housing developed along the enclosure period roads from the later 19th to early 20th centuries – much of it of ‘bylaw terrace’ form.

The oldest part of the Grenoside character area provides some striking contrasts to Ecclesfield. The evidence points towards this being a late medieval unplanned nucleated settlement. The characterisation data notes an absence of burgage type plots, church, or manor. The settlement is not associated with a recorded former open field system and (perhaps tellingly) Grenoside is not recorded as a placename until the 16th and 17th centuries (Smith 1969, 246). The earliest evidence for settlement here is two cruck buildings at Hill Top Farm and Prior Royd Farm (Morley 1984). Cruck construction in South Yorkshire generally dates to the 14th-17th centuries (see Ryder 1979c). The stimulus for Grenoside’s growth was probably as much due to the growth of rural metal working as to agricultural activity. Hey (1991, 83) has noted the growth of likely ‘squatter settlements’ around greens and commons in the post-medieval period, a process he associates with the activities of the emerging class of ‘cutler-farmers’. At Grenoside, Morley (1984) highlights a number of residents listed as members of the Cutlers Company in the 17th century, in addition to a thriving nail making industry. Unplanned squatter development would be expected to result in a highly irregular plan-form of pre-enclosure settlement, such as that depicted here by Jeffreys in 1775. Houses are shown around the edge of and on small assartments within the historic Greno Moor.

The present road pattern is likely to have been laid out by the 1789 Ecclesfield and Greno Wood Enclosure Award (English 1985, 45). It is typical of new road layouts of this period, being straight edged and of regular character. It was probably drawn to formalise property ownership within this growing township. Building phases predating this enclosure period are unlikely to be aligned with the later roads.

Legible evidence of metalworking in Grenoside can be found throughout the historic core of the settlement. Iron founding was developed by the Walker family on Cupola Lane in the 1740s, before their expansion into ever larger premises (with better communications) in Masborough, Rotherham. The name of this lane probably originates in either the air furnaces built here by Aaron Walker or their later cementation furnace, constructed around 1749 (Morley 1984). The Grenoside steelworks remained in the hands of the Walker family until 1823, when they were taken over by the Aston family. By 1825 three separate crucible steelworks are known to have been in operation - one with twelve melting holes on Cupola Lane, eighteen melting holes at Top Side and twelve melting holes on Stephen Lane. Traces of these furnaces survive at Topside and Stephen Lane, but the site of the works at Cupola Lane has been built over. The SMR records a further eight sites of workshops and a file cutting shed in Grenoside, mostly within surviving vernacular buildings.

The improvement of transport communications to Grenoside are represented by the Sheffield-Halifax turnpike built in 1777 (Smith 1997) [now Main Street]. Buildings along this road are largely 19th century in origin and include a Primitive Methodist Church, National School, stone built public houses, inns, and workers housing.

Dore is traditionally thought to be the place where in AD 827 Ecgbert, King of Wessex, met the Northumbrians and accepted their subjection (Hey 1998, 6); the village lies on the boundary between the former Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria (until the 20th century the boundary between Yorkshire and Derbyshire). A well off middle class suburb developed around the village’s historic core from the late 19th century onwards.

The present village retains the probably ancient street pattern shown on the 1835 Sanderson map. The pattern is irregular with little evidence for burgage plots. A number of older stone built vernacular cottages and farmsteads dating from the 17th through to the 19th centuries are retained, with the majority being listed. The 20th century has seen the demolition of some important earlier buildings including the early post-medieval Dore Hall. Important institutional buildings include the listed former village school on Savage Lane (dating to 1821), and Christ Church (dating to 1828), which was built near the site of an ancient chapel of ease. Later suburban expansion outside the historic core preserves little legibility of the former surrounding field patterns, although some ridge and furrow and relict piecemeal enclosure boundaries are preserved in the recreation ground immediately to the west of the village centre.

Like Dore, Mosborough and Beighton, Totley lies within the area of historic Derbyshire rather than Yorkshire. The urban form of the historic core (a typical medieval linear village with a single main street along the present Hillfoot Road and Totley Hall Road) has little changed from its form on the 1877 OS mapping of Derbyshire. Most buildings within this area have survived from this time, with few completely new buildings; most later buildings, (for example 315 -329 Baslow Road, a late Victorian terrace) continue to use vernacular facings and building styles.

The majority of the buildings in this core area date from the 18th and early 19th centuries with much use being made of local building styles, such as the use of sandstone rubble, stone mullions, stone slate roofs and casement windows. The oldest building is probably Cannon Hall, which the English Heritage listing text ascribes in part to the late 16th century, with early 17th century additions. An adjacent cruck framed barn, with possible medieval origins, is recorded on the SMR.

Other important buildings include an early school house (dated 1827, converted to residential use in mid 20th century) and several vernacular farm complexes. Also included in this area is the mansion of Totley Hall, originally built in 1623 in local style and enlarged in a similar style in 1883 and 1894 as an industrialist's residence. The Hall was re-used in the 20th century as part of Sheffield Technical College and is associated with a Hall Farm to the north.

In plan form the village suggests unplanned nucleation, with little evidence on Sanderson's 1835 map for burgage plots. This map does, however, show a clear pattern of strip enclosure around the village, a form often ascribed to the piecemeal enclosure of open fields in the early post-medieval period (Taylor 1975, 120-122). Sanderson's map also shows a small square to the north of the village, a probable green now fossilised by the plot on which stands Ash Cottage.

The centre of the historic village area is crossed by the turnpike road from Sheffield to Baslow, built at the start of the 19th century. The village form, however, suggests that the more historically important route was that which runs from Dore to Woodthorpe.

The suburban growth of both Totley and Dore (which form a common character area) was first stimulated by the construction of the Midland Railway in the early 1870s. By the 1877 1st edition mapping of Derbyshire, the main line of this railway (London via Chesterfield) had been opened, with a station built at Abbeydale Road. A new road (Dore Road) was built to link the station with the historic village and this had become the focus for the development of large detached villas by the 1890s.

The historic core of Stannington appears to have been dispersed over a wide area; the characterisation records a probable medieval road pattern including at least one village green. The historic settlement core includes a number of listed buildings (including some cruck built structures). Suburbanisation appears in Stannington later than in most of the other villages in this zone. Whilst plots were laid out for villa development in the Liberty Hill area in the late 19th century, it was not until the 1920s to 1930s that they are depicted with any number of buildings. The same period, between the wars, appears to have seen development in the Woodland View area of geometric estate housing in the typical municipal cottage estate form - in addition to infilling by privately developed medium density housing around the historic settlement core. Post-war development has seen a continuing mixture of these types with some later large-scale high density municipal housing. Field patterns in Stannington include well preserved early 19th century parliamentary enclosures at Greaves Lane still managed as enclosed agricultural land.

Oughtibridge is another settlement that appears to have grown from settlement around a former common or green. Enclosure of this land, probably by the Hallam Enclosure Award of 1805 (English 1985, 62), appears to have defined the current property boundaries and conditioned the later growth of the village. The oldest historic character in this area, on a landscape scale, is around the junctions of Langsett Road and Church Street, characterised as representative of 19th century development. Otherwise this character area is made up of medium density 20th century suburban extensions to the early core area.

The settlement at Wharncliffe Side probably post-dates the construction of the Wadsley and Langsett Turnpike in 1804-5, as the oldest stone fronted buildings here are generally strung out along this road. Most of the buildings depicted by the OS in 1854 survive, although the vast majority of housing in this area dates to the construction of mid 20th century municipal housing estates. These were expanded with private developments in the late 20th century. Estate development has fossilised no evidence for the earlier piecemeal enclosure landscape.

Worrall, a small nucleated settlement still surrounded by farmland to the west of Sheffield, retains much village form in the historic core around Town Head Road, in addition to a number of vernacular buildings depicted on 1850s OS mapping. This early mapping shows a small unplanned nucleation of farmsteads. Analysis of Harrison’s 1637 survey (Scurfield 1986) shows the settlement was on the edge of moorland common at that time – a niche occupied by many of the villages of the former Bradfield Township. Suburbanisation began between the wars with construction of semi-detached and detached medium density housing around the historic core and to its north. Post-war development has also tended towards medium density development, fossilising little historic legibility outside of the historic core of the settlement.

Enlarged Villages character areas

Map links will open in a new window.

- Dore and Totley Villages (Map)

- Ecclesfield Village (Map)

- Grenoside Village (Map)

- Oughtibridge (Map)

- Stannington (Map)

- Wharncliffe Side (Map)

- Worrall Village (Map)

Bibliography

- Elliot, B.

- c.1958 Thorncliffe: A Short History of Newton Chambers and Co. Ltd. and its People. Chapeltown: Newton Chambers and Co.

- English, B.

- 1985 Yorkshire Enclosure Awards Hull. Hull: University of Hull.

- Jeffreys, T.

- 1775 The County of York. 1 inch: 1 mile.

- Jones, J. and Jones, M.

- 1993 ‘…A Most Enterprising Thing…’ An Illustrated History to Commemorate the 200th Anniversary of Newton Chambers at Thorncliffe, Chapeltown and High Green Archive.

- Hey, D.

- 1979 The Making of South Yorkshire. Ashbourne: Moorland Publishing.

- Hey, D.

- 1991 The Fiery Blades of Hallamshire: Sheffield and its Neighbourhood, 1660-1740. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

- Hey, D.

- 1998 A History of Sheffield. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing.

- Kain, R.J.P. and Oliver, R.R.

- 2004 The Enclosure Maps of England and Wales [online catalogue] Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Available from: http://hds.essex.ac.uk/em/index.html [accessed 8/08/08].

- Miller, W.T.

- 1949 The Water Mills of Sheffield (Fourth edition edited by Allison, A.). Sheffield: Sheffield Trades Historical Society.

- Morley, C.

- 1984 A Short Survey of Historical Grenoside unpublished notes held in SCC Conservation Area files. (Commercially available as Morley, C. Round and About Grenoside Volume 4: Our Village Story Grenoside, Grenoside Local History Group 2005.

- Pevsner, N. and Radcliffe, E.

- 1967 The Buildings of England. Yorkshire: The West Riding. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Richards, R.

- 1991 The Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, Beighton. Beighton, St Mary’s Church.

- Ryder, P.

- 1980 Ecclesfield Priory. Archaeological Journal, 137, 453-454.

- Sanderson, G.

- 2001 Sanderson’s Map: Twenty Miles round Mansfield- 1838. Nottingham and Matlock, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire County Councils.

- Scurfield, G.

- 1986 Seventeenth Century Sheffield and its Environs. The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 58, 147-171.

- SCC

- 1962 Ten Years of Housing in Sheffield. Sheffield: Sheffield Corporation.

- Smith, A.H.

- 1961 The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire: Part One. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, H.

- 1997 Sheffield’s Turnpike Roads. In: M. Jones (ed.), Aspects of Sheffield. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Publishing Ltd, 70-83.

- Stroud, G.

- 1996 The Value of the Fairbank Collection as a resource for the study of landscape change in the parish of Eckington, Derbyshire Dissertation (MA). University of Sheffield.