Sub-Rural Fringe

Summary of Dominant Character

Figure 1: Ecclesall Woods, within Sheffield’s ‘Sub Rural Fringe’, an area where essentially rural characteristics have been preserved, largely for amenity value.

© 2006 Mike Fowkes. Licensed for reuse under a creative commons license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

The historic character of the sub-rural fringe zone is defined by an open landscape with strong rural indicators, such as open space, relict field boundaries, high levels of woodland and a general absence of housing or active industry. Nevertheless, the influence of nearby or surrounding urban settlement has fundamentally altered the character of the land within this zone. All this land has previously been dominated by agricultural or industrial character (sometimes both), however these activities have now generally ceased and the management of these landscapes is largely concerned with maintaining their amenity value as green spaces, whilst encouraging opportunities for recreation and biodiversity. The character areas within this zone feature a wide variety of character types dating to many different periods; as a result, this zone is often one of character transition, areas of sub-rural character often blending or interlocking with adjacent urban landscapes.

A clear difference in the character of these landscapes can be observed between the eastern and the western sides of the city – a difference that reflects not just topographic and geological changes but also the social patterning of the city’s demographic makeup. In the west of the city, for example in the parklands of Norton, in the Porter valley and at Beauchief, suburban expansion for housing growth was balanced by explicit moves to protect greener landscapes. The efforts of J.G. Graves, who purchased the former Shore estate of Norton Hall and presented it to the city in phases between 1925 and 1935 (SCC 1977) as Graves Park - a “gift to the Corporation to be maintained as a public park for the use and enjoyment of the citizens for ever” (J.G. Graves quoted in Sewell 1996, 115), is an example of this. Similar moves by the Corporation of Sheffield and bodies such as the Sheffield Town Trust formed the basis of the preservation of the Porter valley parks, Ecclesall Woods, Millhouses Park, Abbeydale Works and land within the Rivelin Valley.

Figure 2: Abbeydale Works, a water powered scythe and steel works preserved as a museum in the mid 20th century.

© 2003 Alan Fleming and licensed for reuse under a creative commons license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

By contrast, in the east of the city much of this zone has emerged as recreational amenity land only since the late 20th century. Former large-scale industrial landscapes dominate much of the sub-rural fringe in this area. For example, around Handsworth and Woodhouse large areas were formerly occupied by coal mines and their associated spoil heaps. This land generally still has legible traces of former extractive activities, although substantial efforts have been made (particularly in the last ten to fifteen years) to introduce management regimes to improve these environments.

Inherited Character

The Western Fringes

Character areas in the west of this zone generally contain older and better preserved historic landscapes and associated features, with large areas of the landscape stabilised in terms of use and management by at least the early 20th century. In the east of the zone, surviving pre-20th century historic landscape features are more likely to be isolated as islands within dynamic ‘regenerating’ landscapes.

One of the most stable landscape types within the western part of the zone is probably ancient woodland, including substantial areas at Wharncliffe, Ecclesall, Trippet and Endcliffe woods, as well as further smaller ancient woodlands associated with historic parklands around Beauchief, Millhouses and Norton. The majority of woodlands in this zone are described in the Natural England Woodland Inventory as ‘Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland’ i.e. they are “composed predominantly of trees and shrubs native to the site that do not obviously originate from planting” (Goldberg and Kirkby 2002, 7). These woodlands are often preserved on steeply sloping sites historically unsuitable for large-scale agricultural, industrial or residential exploitation. Earthworks connected with woodland management, such as charcoal and whitecoal burning hearths, and small-scale mineral extraction, often evidenced by the annular spoil heaps characteristic of bell pit mining, are common. Ecclesall Woods also contain traces of an older landscape, in the form of a hilltop enclosure and field boundaries potentially dating from the Iron Age / Romano-British periods (A.S.E. Ltd. 2002).

This zone also features some of most legible traces of medieval landscapes within Sheffield, in the remains of Beauchief Abbey and Sheffield Manor Lodge. Beauchief Abbey lies within extensive parkland that was probably land taken out of cultivation in the mid 17th century. Within this parkland remains of ridge and furrow earthworks and associated hollow-way tracks can be seen (Merrony 1994, 66-67). Manor Lodge, first built as a hunting lodge for the medieval Dukes of Norfolk, was converted into a fine country house in the 16th century (Hey 1998, 14). The remains lie in the smallest character area classified as ‘sub-rural fringe’ – an area that includes irregular fields and two farmsteads probably dating to the enclosure of the medieval deer park as farmland in the late 17th and early 18th centuries (Douglas 2006, 9).

The ornamentalisation of the western fringes of the city began in the 18th century with the emparkment and embellishment of landscapes at Norton Park, Oakes Park, Beauchief Hall and Park, and Whitely Wood Hall. Of these, Oakes Park and Beauchief Hall (including the medieval remains of the Abbey landscape), are considered significant enough examples of 18th century parkland to be included on the English Heritage Register of Parks & Gardens of Special Historic Interest (English Heritage 2004).

This parkland tradition continued with the acquisition of steeply sloping land to the south of the Porter Brook by the General Cemetery Company in 1836 (Sewell 1996, 181). The company employed Samuel Worth to design a picturesque landscape of sweeping drives amongst evergreen trees adorned with temple-style chapels and gateways influenced by Greek and Egyptian architecture (Harman and Minnis 2004, 226). The cemetery, originally built for non-conformist burials, was extended in 1848-50 for Anglican burial – the newly provided cemetery chapel for this separately enclosed area adopting a noticeably more traditional Decorated Gothic style (ibid, 228). The cemetery, which is included on the English Heritage Register, fell into disrepair during the 20th century and passed into the hands of Sheffield City Council in 1977, who have since entrusted its management to a local friends group.

The sub-rural fringe includes much of the valley bottoms of Sheffield’s smaller rivers: the rivers Loxley, Rivelin and Sheaf, and the Porter Brook. Closer to the city centre, the same river valleys have generally been included in the ‘Post Industrial’ character zone. These valleys are all rich in remains of water-powered sites, most of which were utilised until the late 19th century for the forging or grinding of edge tools (see Crossley ed. 1989 and Miller 1949 for site by site accounts).

Figure 3: The legacy of water-power has left a rich heritage of industrial remains in the western valleys, such as this dramatic overflow from ‘Forge Dam’ on the Porter Brook.

© 2006 James Hobbs. Licensed for reuse under a creative commons license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Water-power is known to have been utilised by the monks of Beauchief on at least five sites on the Sheaf before 1300: at New Mill (1180), Millhouses (also known as Eccelsall Corn Mill – 1250), Walk Mill (1250), Moscar (1280), and Bradway Mill (1280) (Mott 1969, 212). It is generally considered that the early use of water-power in the region was largely for the milling of corn. The earliest reference to metal grinding (thought to relate to Moscar Wheel) was made in 1496 (Crossley et al 1989, vii), although this may be the result of few manorial rental records surviving locally from before 1581 (ibid).

The mills in these valleys are regularly depicted on historic plans, such as those held in the Fairbank Collection at Sheffield Archives, and can be seen to tend towards a characteristic and formulaic layout. This typically consisted of a weir diverting flow from the river along a channel (known locally as a head goit) leading to a pond (known locally as a dam). Dams were often created by quarrying into the hillside adjacent to the river and using the spoil to create an embankment to impound the diverted water.

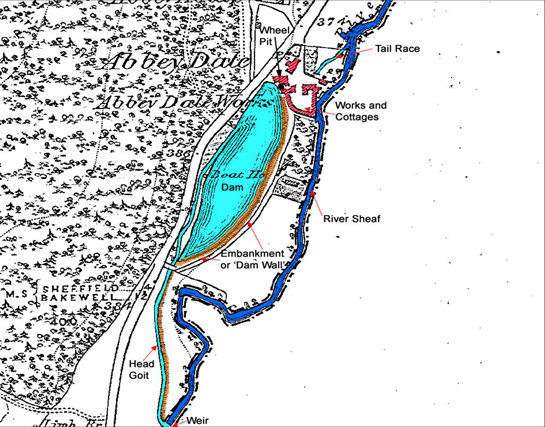

Figure 4: Abbeydale Works (based on the 1852 OS map), showing the typical layout of a Sheffield ‘bypass-system’ water-powered works. Abbeydale Works was purchased for the city by J.G.Graves in 1935 but not opened in a restored state until 1970 (Crossley 1989, 98-99)

Image © SYAS 2008 based on out of copyright OS

At the tail end of the dam the water would enter a forebay, where it would exit the dam and flow into the pentrough - a wooden or metal box used to control the flow of water to the wheel. The wheel itself would generally be mounted in a wheel pit constructed of stone blocks. A building adjacent to the wheel pit housed the powered processes, which could include grinding, forging, rolling, and slitting. Below the works buildings there is typically a tail goit, sometimes of great length, designed to drain water swiftly from below the wheel pit and return it to the river without impeding the efficiency of the turning wheel. By the later 19th century the main wheel building is often accompanied at larger sites by various combinations of ancillary workshops, hand forges, furnaces, etc. Domestic cottages are also common adjacent to the industrial buildings and are often arranged around a courtyard.

Steam began to supplant water-power in the mid 19th century, with a gradual abandonment of water-power in the valleys of the Porter, Sheaf, Rivelin and Don. It is notable, however, that water-powered mills continued to be built and maintained on the River Loxley well after the devastation of the valley following the failure of the Dale Dike Dam in 1864 (Crossley et al 1989, ix). This maintenance of water-power has been ascribed in part to the “value of a guaranteed supply of compensation water” (Cass 1989, 29-37), as the Water Company undertook to maintain a constant flow of water to mill sites in this valley, in compensation for the construction of reservoirs in its catchment. It is also possible that the flow of capital resulting from claims for damages from the flood also provided opportunities to invest in existing facilities.

Preservation of water-powered sites in this zone varies from the outstanding, at sites such as Abbeydale Works on the river Sheaf, and Shepherd Wheel on the Porter Brook (both preserved as museums), to the invisible - where dams have silted up, buildings have been cleared and sites have been levelled or over-built. Many mill sites in this zone are, however, legible to some extent, with a number of weirs and dams in some kind of water holding condition. At least eleven water-holding dams are under the management of Sheffield City Council’s Parks and Countryside service in the Porter valley parks and the Rivelin Valley, with a further thirteen silted up and overgrown dams in the SCC owned section of this valley (Sheffield City Council 2005). These water bodies provide substantial legibility of the valleys’ former industrial character.

The later 19th and early 20th centuries saw significant moves to protect stretches of the Porter, Sheaf and Rivelin Valleys in which industrial activity had ceased. The first steps of this process saw the acquisition of Endcliffe Wood by the Corporation in 1885, partly to improve the transport of sewage away from the expanding housing area of Ranmoor, and partly to provide amenity land (Sewell 1996, 42). The initial area, landscaped by the nationally acclaimed William Goldring, was expanded by the acquisition of further land by the Corporation (with the assistance of generous individuals and charitable trusts) in 1888, 1897/8, 1911, 1913, 1927,1932 and 1937 until the whole of the present linear ‘Porter Valley Parklands’ system was established (ibid, 42-43). The former mill dams of Endcliffe, Holmes and Nether Spur Gear Wheels were converted by Goldring to use for bathing, skating and waterfowl respectively (English Heritage 2004b – entry GD3344).

The Corporation established the Rivelin valley as a public open space following its purchase in 1934 (Sewell 1996, 146). Its former industrial sites do not survive as well as those in the Porter valley because buildings were largely cleared during the 1940s and 1950s (ibid), although many legible remains of goits, weirs and dams remain.

Ornamental use of the Sheaf valley at Beauchief Park and Ecclesall Woods has already been noted. The preserved Abbeydale Works remains the only significantly legible water-powered site in this character area. Landscaping of Millhouses Park (by Sheffield Corporation in the early 20th century) removed most traces of the dams and goits of Skargell / Bartin Wheel and Millhouses Corn Mill, although a complex of buildings from later phases of Millhouses Corn mill does survive, reused as a park store.

The Eastern Fringes

Character areas in the east of this zone are generally influenced by the former presence of heavy industries dating to the 19th to 20th centuries.

‘Chapeltown Woodlands’ are an excellent example of this type of landscape. Historically, the ancient broadleaved woodlands of Thorncliffe, Parkin, Hesley and Smithy Woods covered this area. Ordnance Survey maps of 1855 show a substantial extractive and industrial landscape, concerned with the processing of ironstone, within these woodlands. Numerous annular spoil heaps are indicated, in addition to at least 4 collieries and the iron works of Chapeltown and Thorncliffe. These industrial activities, which would see massive growth by the mid 20th century, were all connected with the ironworks and coal tar refineries of Newton Chambers, established in 1793 (Jones 1999, 148). This concern, which arguably led to the development of much of Chapeltown and High Green, was active until 1981 (ibid). Significant legibility remains in this area of these former extractive sites (notably the remains of Smithy Wood Colliery).

Later Characteristics

The ‘Handsworth and Woodhouse Relict Countryside’ character area consists of land encircled from the west by housing development. Where agricultural land use continues, it is frequently characterised by the loss of historic boundaries - to create larger units - over the second half of the 20th century. Extractive and post-extractive (where sites have been reused following the cessation of extraction) industries are never far away, with the eastern boundary of the zone generally formed by the historically extractive Rother Valley. The Shire Brook valley (to the south east of the city) is particularly dominated by post-extractive influences, featuring the former site of Birley East Colliery, opened in 1907 and present until 1988 (although for much of this period active only as a pumping station). The site has recently been planted with trees, to increase its amenity value.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Abbeydale and Millhouses (Map)

- Chapletown Woodlands (Map)

- Loxley and Lower Rivelin Valleys (Map)

- Manor Lane (Map)

- Norton Village and Parklands (Map)

- Porter Valley Parklands (Map)

- Porter Valley at Sharrow Vale (Map)

- Wharncliffe Woods and Deepcar Don Valley (Map)

- Woodhouse and Handsworth Relict Countryside (Map)

Bibliography

- A.S.E. Ltd.

- 2002 Hilltop Enclosure and Field System. Ecclesall Woods, Sheffield: Archaeological Survey. [unpublished]. Oxford: Archaeological Survey and Evaluation Ltd. Rep no AS-02.

- Cass, J.

- 1989 The Flood Claims: A Postscript to the Sheffield Flood of March 11/12th, 1864. Transactions of the Hunter Society, Vol 15 (1989), 29-37.

- Crossley, D. (ed) with, Cass J., Flavell, N. and Turner, C.

- 1989 Water Power on the Sheffield Rivers. Sheffield: Sheffield Trades Historical Society with University of Sheffield Division of Continuing Education.

- Douglas, M.

- 2006 Manor Oaks Farm, Manor Lane, Sheffield: Interim Report on Archaeological Building Recording. [unpublished] Sheffield, ARCUS report number 837b.2

- English Heritage

- 2004 Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England – South Yorkshire (Revised) [unpublished]. London: English Heritage ref: GD 00037/RUP

- Goldberg, E. and Kirby, K.

- 2002 Ancient Woodland: Guidance Material for Local Authorities. Peterborough, English Nature.

- Hey, D.

- 1998 A History of Sheffield. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing Ltd.

- Harman, R. and Minnis, J.

- 2004 Sheffield: Pevsner Architectural Guide. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Jones, J.

- 1999 An Illustrated History of Izal. In: M. Jones (ed.), Aspects of Sheffield 2: Discovering Local History. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Publishing Ltd, 148-163.

- Merrony, C.

- 1994 More than meets the eye? A Preliminary Discussion of the Archaeological Remains of Beauchief Abbey and Park. In: C.G. Cumberpatch and S.P. Whiteley (eds.), Archaeology in South Yorkshire 1993-1994 Sheffield: South Yorkshire Archaeology Service.

- Miller, W.T.

- 1949 The Water Mills of Sheffield. Fourth edition. A. Allison (ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Trades Historical Society.

- Mott, R.A.

- 1969 The Water Mills of Beauchief Abbey. Transactions of the Hunter Archaeology Society, Vol 9 (pt 4), 203-220.

- NAA

- 2001 Fuelling the Revolution: The Woods that Founded the Steel Country. Sheffield Archaeological Surveys: Volume II – Level 2 and 3 Survey Woodlands [unpublished]. Barnard Castle: Northern Archaeological Associates. Report no NAA01/106.

- Sewell, J.

- 1996 A Strategy for the Heritage Parks and Green Spaces of Sheffield [unpublished]. Sheffield City Council Leisure Services Directorate.

- SCC

- 1997 Sheffield Historic Parks and Gardens: UDP Policy Background Paper no 4. [unpublished document by SCC officers available for consultation via SMR office.

- SCC

- 2005 Condition of the City’s Dams [unpublished]. Report by Sheffield City Council Premises and Assets management team to Culture, Economy and Sustainability Scrutiny and Policy Development Board meeting 19th May, 2005. Available from: www.sheffield.gov.uk [accessed 03/07/2007].