Late 20th Century Replanned Centres

Summary of Dominant Character

Figure 1: Telephone House, built in 1972 above a brutalist inspired car park, is typical of the architecture originally built around the 20th century urban dual carriageways of this zone.

© 2007 SYAS

The character areas making up this zone generally underwent fundamental character change in the period 1945-1977. The dominant theme of this change was urban renewal. Areas were generally cleared wholesale of earlier buildings and features, and street patterns were reconfigured. These clearance projects are generally contemporary with those that produced the ‘Late 20th Century Municipal Suburbs’ zone. Indeed this zone includes the sites of the high density inner city housing projects (all built on cleared terraced housing sites) of Hanover, Lansdowne, Netherthorpe, as well as the redeveloped site of the Broomhall Flats. The zone also has architectural affinities with parts of the Historic Core zone, where post-war urban renewal replaced large areas of buildings, but left street patterns intact, such as around High Street and West Bar/ West Bar Green.

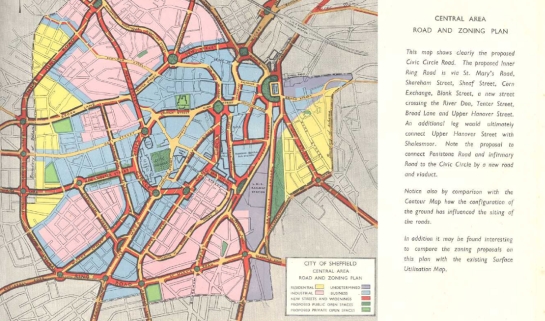

Figure 2: ‘The 20th Century Replanned Centre’ of Sheffield is defined as those areas of the city centre subject to major clearance and redevelopment, connected to the realignment of the city’s road system, central housing schemes and the development of higher educational institutions in the mid to late 20th century.

© Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007

The character areas of this zone are linked by a system of roads that were designed as urban dual carriageways (although some have now had central reservations removed), which pedestrians were generally discouraged to cross at surface level. To facilitate crossing, a large number of pedestrian bridges and subways were built, especially at roundabouts. Many of the structures constructed during this period were designed to be uncompromisingly modern in appearance, with much influence of the Brutalist school of architecture evident (Harman and Minnis 2004, 209).

The title of this character zone acknowledges the importance of the proposals published by the City Council Town Planning Committee at the end of World War II (Sheffield City Council 1945). These proposals, entitled Sheffield Replanned, presented the findings of an investigation by the City Engineer’s department into reconstruction possibilities following the devastating air raids on the city in December 1940. The proposals were far reaching - the changes to the road network alone were outlined in a 50-year schedule (ibid, 73-74). The specifics of the resulting developments often differed from the initial proposals, however, the original document laid out many principles that formed dominant themes in the development of the city centre until the present day. The proposed land-use zoning laid out a basic land-use pattern for the city centre that would continue until the early twenty first century. The present dual carriageway inner ring road and an inner civic circle (only partly built) were both proposed. The civic circle idea was to be revisited in the later 1960s, with the construction of a complete loop comprising Eyre Street, Furnival Gate, Charter Row and Furnival Gate. The segregation of pedestrians and traffic, which would became so characteristic of this zone, was envisioned - with barriers along central reservations working in concert with road crossings provided at approved points and in “subway crossings (perhaps improved by the installation of escalators) at the more important traffic roundabouts...” (ibid, 46).

Figure 3: A surviving subway crossing under Charter Square on the Civic Circle

© 2006 SYAS

Other proposals of Sheffield Replanned that influenced much of the dramatic replanning of this zone included plans for: a Town Hall extension; a Bus Station (replacing a tram system seen as incompatible with the new ‘gyratory’ road system); a Technical College, overlooking the bus station (now the Sheffield Hallam University City Campus); a combined and centralised theatre and cinema area; the pedestrianisation of the city centre; the removal of heavy industry from the ‘Ponds’ character area; and the removal of existing housing from the city centre. The influence of Sheffield Replanned would also be felt outside this zone – the document foresaw the redevelopment of the High Street and Castle character area, although this development was eventually accommodated mostly within the historic street pattern.

Figure 4: Extract from ‘Sheffield Replanned’ (SCC, 1945)

© SYAS

Largely outside the direct sphere of influence of the city council’s schemes, but intimately linked with them, are significant developments by the University of Sheffield, the NHS and Sheffield Hallam University (and its predecessors). The City Campus of Sheffield Hallam University has already been mentioned and has its origins in the Technical College proposed in Sheffield Replanned. Originally built by Sheffield City Council, as part of its obligation under the 1944 Education Act, the earliest surviving parts are the Owen, Surrey and Norfolk Buildings built 1953-1968 (Harman and Minnis, 2004, 89).

Figure 5: Sheffield University’s Arts Tower

© 2005 David Gill. Licensed for reuse under a creative commons license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

The University of Sheffield was originally established around the former Technical School on Mappin Street, but soon expanded westwards - after the acquisition of land and the construction of Firth Court at Western Bank in 1902-1909. Significant expansion of these early buildings occurred in the same period as development of the rest of this zone. The Western Bank site is now dominated by the Library and 21 storey Arts Tower (1955-1965), designed as complementary linked buildings. The rest of the University buildings are united by the ‘Concourse’, a pedestrian space designed to bring buildings together despite the presence of a main road bisecting the site. This division was complicated in the mid-late 1960s by the upgrading of the road to dual carriageways, as a main feeder into the Inner Ring Road – a challenge met by construction of a concrete flyover carrying the road overhead. Other buildings on the site are of a variety of twentieth century styles, often rising to 5 or more storeys.

To the west of Sheffield University lies a significant and large complex of NHS hospitals. Although the oldest phase of the Children’s Hospital dates to 1902, it was massively expanded from the late 1960s onwards in modern style. Three major hospitals, all now affiliated to the University School of Medicine as teaching establishments, are sited here. The most characteristic building within this complex is the massively built concrete Royal Hallamshire Hospital.

Inherited Character

The defining characteristic of this zone is the extent to which earlier urban environments have been re-written. This means that the different landscapes and street patterns that existed in this zone prior to replanning have left very few legible remains.

A significant feature of the replanning of the centre of Sheffield was the construction of Civic Circle and its associated roundabouts and underpasses – including the ‘Hole in the Road’, which lay at the head of the ‘Civic Circle’ character area and is discussed within the ‘Historic Core’ zone. Along Arundel Gate and Eyre Street the Civic Circle cut through an area historically divided into a grid of streets occupied by mixed light industry and housing, which had grown up around the historic core in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. (Surviving examples of this type of development are found in the ‘18th-19th Industrial Grids’ zone.)

Figure 6: Construction work on Arundel Gate 1967

© SCC

The 18th and 19th century grid pattern here had developed after the 1788 enclosure of the former Little Sheffield Moor. The central axis of The Moor, within the modern shopping centre, is now the only legible trace of this triangular common; the central street fossilises South Street, which was laid out by the Ecclesall Enclosure Award as a 60 foot enclosure road down the centre of the common. The triangular pattern of the earlier moor, which had survived within the later street pattern, was lost post-war in favour of a rectangle, which was eventually bounded and sealed by the Civic Circle and its subways in the late 1960s.

Further areas of 18th-19th century industrial grid development were lost to the east of the city centre, with the redevelopment of the theatre and cinema complex (originally known as the Epic development (Harman and Minnis 2004, 152)). This redevelopment featured large windowless blocks, massive car parks, and extensive networks of internal public rights of way directed through subways, deck-style walkways and escalators. This area also provided land for the Town Hall extension, originally proposed in Sheffield Replanned for the site of the present Peace Gardens, but eventually constructed further to the east in the late 1970s.

The ‘Ponds’ character area lies within the valley floor formed by the combined alluvial plains of the rivers Sheaf and Porter. Historically this area was probably low lying meadow land and mill sites are known here from the medieval period onwards. Some haphazard industrial suburbanisation appears to have already begun by 1736. The area was comprehensively redeveloped in the 20th century, including the construction of the Bus Station in the 1950s, although the recommendation in Sheffield Replanned that heavy industry be removed from this area was not fully implemented until the demolition of the remains of Pond’s Forge and other steel works in advance of the 1991 World Student Games. The only earlier legible features are the timber framed sections of the ‘Old Queens Head’, originally part of a medieval elite property and, from the late 19th century, the Midland Railway Station and the gateway from the Ponds Forge works.

The ‘Lansdowne, Hanover, Netherthorpe and Inner Ring Road’ character area dates principally to the 1960s and 1970s and includes the sites of three surviving and one demolished inner city municipal housing projects. These housing estates were all built to replace condemned mid 19th century working class housing. As a rule, none of these estates fossilised earlier street patterns and the forms of housing introduced represented radical changes in the patterns of urban living. However, the deck access system and continuation of earlier street names at Lansdowne continued the attempt at replicating some of the character of street life begun at Park Hill. The estates are all adjacent to parts of the Inner Ring Road, the construction of which often involved the demolition of at least one street. The construction of the road caused severance of parts of the industrial district to the south of the city centre, as well as of the 18th-19th century suburb of Broomspring (originally a continuous part of Broomhall) and of the two central sites of the University of Sheffield.

Figure 7: Demolition of Aberdeen Street in Broomhall in advance of the construction of the inner ring road and Hanover Estate in 1964 – with the half built University Arts Tower in the background

© SCC

The more piecemeal development of Sheffield University’s buildings and the hospitals within the ‘Western Bank’ and ‘St George’s’ character areas preserves the most historic legibility within this zone. Much of the older street patterning, established by the late 18th century and developed along grid-iron lines, is retained. Some important 19th century houses, churches, industrial buildings and the neo-gothic former Jessop’s Hospital for Women survive. At Western Bank, clearance and demolition has left little historic fabric, in what was formerly one of the oldest parts of the suburbs of Broomhall and Crookes. However, the earliest building phases of the Children’s Hospital and University predate the most characteristic period of development of this zone.

Later Characteristics

This zone has been discussed in terms of the landscape created by large-scale urban renewal and road projects undertaken in the period from 1945-1977. By the early 1980s Sheffield’s traditional industries of both heavy steel and light tool production were in serious and near terminal recession (Hey 1997, 238-244). The loss of Council revenue from business taxes as the industrial base of the city collapsed, combined with falls in central government grants (ibid, 245), meant that little spare cash was available for the maintenance of newly created municipal assets in this zone. The brutalist aesthetic of these developments, so promoted by successive city architects and engineers, began to become a symbol of the decline of the city and country at large. This period saw the rise of a new role for architecture and urban design, often characterised as ‘regeneration’. Within this zone, early signs of this process include the construction of the Moorfoot building in 1978, built for the former Manpower Services Commission (Harman and Minnis 2004, 100), as part of a government drive to relocate parts of the civil service to the regions.

The mid 1990s saw the genesis of the ‘Heart of the City’ project, with ambitious plans drawn up to reconfigure the city centre. These centred around the demolition of the Town Hall extension and Registry Office, freeing up a large, central council owned site for mixed commercial and public development. The ambitious plans, which included an explicit aim for the “removal of severance” (Topwood 1999, 78) caused by Arundel Gate, featured a mix of innovative public open spaces (including the Winter and Millenium Galleries, incorporating covered public rights of way) and commercial development (such as the St Paul’s hotel). The segregation of pedestrians and vehicles has also been reduced, with the re-introduction of surface crossings to Arundel Gate, Eyre Street, Furnival Gate and Rockingham Gate, and the removal of pedestrian bridges around the Moor. Along Arundel Gate, the extensive subway system has been closed and filled, most notably at Furnival Square, where a monumental grade separated underpass formerly dominated the townscape.

Figure 8: The early 21st century saw the demolition of the 1970s Town Hall extension, popularly known as ‘The Egg Box’.

© SYAS 2001

In 2007 developments are also continuing within the St George’s and Western Bank character areas as Sheffield University continues to expand.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Civic Circle (Map)

- Lansdowne, Hanover, Netherthorpe and Inner Ring Road (Map)

- Ponds (Map)

- University of Sheffield (St Georges) (Map)

- University Of Sheffield and Hospitals (Weston Bank) (Map)

Bibliography

- SCC (Sheffield City Council)

- 1945 Sheffield Replanned: A Report, with plates, diagrams and illustrations, setting out the problems in re-planning the city and the proposals of the Sheffield Town Planning Committee. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

- Harman, R. and Minnis, J.

- 2004 Sheffield: Pevsner Architectural Guide. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Hey, D.

- 1997 A History of Sheffield. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing Ltd.

- Topwood, A.

- 1999 The Heart of the City. Private Finance Initiative Journal, Vol 4, Issue 4, 78-79.