Complex Historic Town Cores

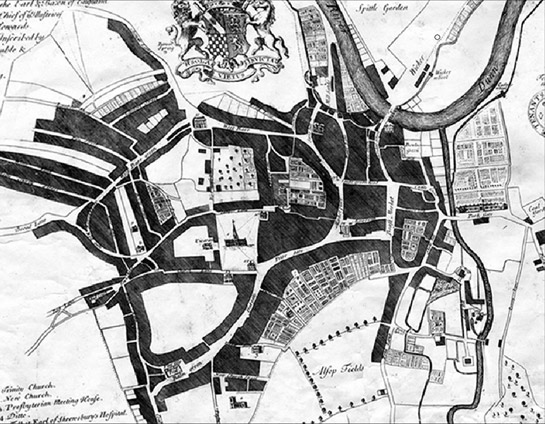

Figure 1a: (above) Ralph Gosling’s map of Sheffield shows the extent of the town by 1737.

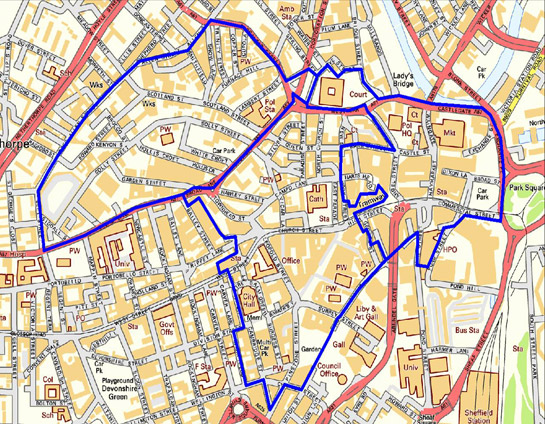

Figure 1b: (below) shows the Character Areas making up the ‘Historic Core Zone’, which closely correspond to this early town. Outside this zone the urban character of the city centre has developed since the mid 18th century.

© OS map Crown Copyright. All Rights Reserved. Other data © SYAS 2007

Current Character Development

This zone includes three character areas in the centre of the modern City of Sheffield, the later development of which has retained an underlying semi-regular street pattern of medieval to post-medieval date. The zone is based on the area shown as developed by the time of Gosling’s survey of the town in 1736. To the south of West Bar / Tenter Street and to the east of Pinstone Street and Townhead, this settlement is likely to have developed during the medieval period, with streets to the west and north known to be post-medieval in origin.

The use of this area as the commercial and social centre of Sheffield can be traced back at least as far as 1296, when the right of the township to hold a market was first confirmed by a royal charter (Hey 1998, 1). The market developed in the first instance in the yard of the castle and was controlled by the lord of the manor of Sheffield until 1899 (AHP 2003, 14). The following year, the lord of the manor confirmed the rights of a group of prominent townspeople (later known as the ‘Church Burgesses and Town Trust’) to administer urban affairs and, crucially, much of the property within the town.

Whilst the cutlery industry is known to have been in existence by the 13th century (Harman and Minnis 2003, 6), it is known to have undergone significant expansion in the 16th and 17th centuries with many new mills built on the Don and its tributaries in this period (Crossley et al 1989, vii). Estimates of the population of the town during the same period indicate a considerable expansion from an estimated 2,200 in 1600; to 3,500 by 1700; and 9,695 by the time of Gosling’s survey in 1736 (Pollard 1956, 172). This growth in population was reflected in the expansion of the physical town. On one front the larger population was accommodated by increasing the building density on existing burgage plots, such as one in Fargate where smithies, houses, offices and outbuildings were all said to be newly erected in 1722 (Hey 1991, 88). On another front, new building plots were laid out on the remaining open land within the existing settlement (for example around the parish church) and on agricultural land immediately surrounding the town in the control of the Church Burgesses and Town Trust (examples being the fields making up the present ‘Crofts’ character area and land west of Fargate, around Barkers Pool).

The 18th century saw not just urban expansion, but also notable renewal of the built environment of the town core. One visitor in 1725 remarked upon the introduction of a fashionable new material to the town, “There has been a great part of the town, which was made up chiefly of wooden houses, rebuilt within these few years, and now makes no mean figure in brick…” (cited in Hey 1991, 84).

Industrial activities were present in close proximity to residential development, leading to Daniel Defoe’s comment in 1710-1712 that, “the streets [are] narrow, and the houses dark and black, occasioned by the continued smoke of the forges, which are always at work” (cited in Hey 1991, 62).

The smoky environment of Sheffield, resulting from the large number of small hand forges or smithies in the town, was compounded in the first two decades of the eighteenth century by the introduction of the cementation furnace; the earliest known sites being at Blind Lane (near Barkers Pool) and Steelhouse Lane (just outside the ‘Crofts’) (Belford 2003, 4). During the 18th century more cementation furnaces (used for converting iron into steel) are known to have been built at Castle Green, High Street, Fargate, Holly Street and Barkers Pool, all to the south of West Bar. No substantial new steel-making sites are known to have been developed in the ‘Heart and Cathedral’ or High Street and Castle’ character areas after the 1880s (ibid, 37-38); it is likely that the already high-density development in these areas made it unsuitable for the laying out of larger integrated steel making and refining complexes. In the ‘Crofts’ character area, in contrast, industrial activity appears to have continued beyond the 18th century, with steel makers and refiners generally expanding their established capacity. However, later new works tended to be concentrated outside this zone, in the areas laid out in grid patterns from the late 18th century onwards. Nevertheless, the ‘Crofts’ area retained a mixed industrial and residential character until well into the 20th century (when much of the housing was cleared).

By the 19th century much of the present street pattern of this zone was well established. Major changes to this pattern, beyond the piecemeal renewal and modernisation of individual buildings, did not begin until the later 19th century, when the Corporation undertook a programme of street widening that would result in the rebuilding of much of High Street, Fargate, Pinstone Street and Cambridge Street, as well as the establishment of Leopold Street, which cut through the medieval street pattern.

Leopold Street became a major administrative focus, with offices for the Education department, Firth College, the Medical School, the Central School and the Assay Office located there. Nearby, in Pinstone Street, a new Town Hall was opened adjacent to St Paul’s Church in 1897(AHP 2003, 11). These developments represent a move away from the direct practice of the industrial activities that had first supported and stimulated the growth of the town, towards the administrative, financial and institutional concerns of the modern city. However, industrial premises such as the cutlery and edge tool workshops of the little mesters, and small steel makers, continued to occupy the fringes of this zone.

The architecture of the emerging city centre (city status was granted by Queen Victoria in 1893 (Hey 1998, 147)) showed a new economic confidence; a mixture of decorative gothic and classical influenced forms were used for facades that increasingly made use of high status stone, often featuring fine relief carvings, as well as smoke resistant glazed materials such as faience (Harman and Minnis 2004, 28). Notably, however, most buildings continued to be constructed by locally, rather than nationally prominent architects (AHP 2003, 11), perhaps reflecting a continued insularity in the city’s cultural outlook.

Twentieth century development continued the trend established by the 19th century, of civic renewal and rebuilding. In the inter war years, substantial programmes of demolition were undertaken - particularly of housing within the Crofts area, which had been portrayed (albeit by outsiders) for some decades as a ‘slum’ area. In the words of one late 19th century visitor to the town “the general darkness and dirt of the whole scene serves but to create feelings of repugnance and even horror” (J.S. Fletcher 1899 cited in Belford 2001, 107). Clearance was intended to provide space for new industrial buildings, however, much of this area has remained undeveloped ever since.

Elsewhere in the city civic improvement between the wars focussed on the creation of public buildings, including the Graves Art Gallery / City Library and City Hall. This period also saw the demolition of St Paul’s church, in 1938. The open space created by the demolition of St Paul’s was officially named the Peace Gardens in the early 1980s, having been known as such by the people of Sheffield for many years. The site was first envisaged as a public open space in 1938, in commemoration of the ill-fated Munich Agreement between Chamberlain and Hitler, which coincided with its creation (Harman and Minnis 2004, 95).

World War II resulted in significant destruction of much of the ‘High Street and Castle’ character area and the vast majority of buildings in this area post-date 1945. Bomb damage included the destruction of every building in Angel Street and King Street and much of High Street, including the Marples Hotel where 70 civilians were killed whilst sheltering in its cellars on the night of December 12th 1940 (Hey 1997, 227). The area was rebuilt in Modernist style and architecturally is similar to the ‘Civic Circle’ character area.

Development of this zone in the past twenty years has concentrated on improvements to the public realm, for instance redesign of the Peace Gardens, and the increased prioritisation of pedestrians over cars. At street level shop frontages have tended towards the national (and international) uniformity of branding, plate glass and illumination that can be seen in all modern cities.

Legibility

The earliest developments of the medieval town are largely within the ‘Heart and Cathedral’ and ‘High Street and Castle’ character areas. As noted above, these areas still form the commercial and public core of the modern city with major features such as the Town Hall, the City Hall, the Cutlers Hall, the Cathedral and the historic markets still sited here. Much of the street plan here is likely to date to the medieval period, with Fargate, Church Street and High Street representing an area of former planned burgage plots, whilst Angel Street, High Street, Castle Street, Haymarket and Dixon Lane fossilise both the early ditches of the castle bailey and the early layout of the market place. Very little visibly survives of the built fabric of the medieval town beyond these fossilised patterns - the earliest surviving architecture is that of the former parish church (since 1914, Sheffield Cathedral), which includes some fine Perpendicular work from the 15th century, within later 19th and 20th century extensions. Archaeologically, other fragments of medieval Sheffield have been identified in these areas, on Broad Lane and Fargate, although generally these remains are heavily truncated.

Of the areas in this zone, ‘Heart and Cathedral’ retains the most pre 20th century character, with important 18th – 19th century survivals to the north of the Cathedral. This area was laid out as a fashionable residential quarter by bankers and capitalists benefiting from the growth of the city’s traditional industries. The earliest example of the gentrification of the area is Old Bank House, the oldest brick house in the city, which was built in 1728 by a Quaker merchant called Nicholas Broadbent (Harman and Minnis 2004, 111). The area was further enhanced during the 18th century by the laying out of East Parade and Paradise Square by various developers. Both of these developments were infilling open spaces between Church Street and West Bar.

Figure 2: Paradise Square, Sheffield - an 18th century development on the edge of the then town centre

© 2002 SYAS

Much of the remaining built form of the ‘Heart and Cathedral’ area is representative of the later 19th and earlier 20th centuries, with many fine Victorian and Edwardian commercial and institutional buildings along Fargate, Pinstone Street, Norfolk Street, High Street and Church Street.

In the ‘Crofts’ character area, development within the plots formed by former narrow fields appears to have been little regulated, with historic mapping showing a high density mix of steel production and other industrial complexes alongside residential buildings until the early 20th century. Early residential buildings are now rare, as a result of clearance programmes. The John Watts’ cutlery works on Lambert Street contains rare exceptions, having absorbed five 18th-19th century domestic courts as it grew. This character area also preserves a number of late 19th century public houses and a few institutional buildings spared during clearance. The most notable historic legibility within this area is the curving line of the streets and of property boundaries, which fossilise the shapes of post-medieval fields, formed by enclosing strips within a former open or town field.

Figure 3: John Watts Works on Lambert Street includes rare surviving domestic buildings

© 2002 SYAS

Later Characteristics

Recently, the open spaces of the ‘Heart and Cathedral’ character area have been the focus of redesign, with Fargate pedestrianised in 1971 and redesigned in 1997/1998 (Sheffield City Council 2004c, 29); the comprehensive landscaping of the Peace Gardens in the late 1990s; and the redesign of Barkers Pool in 2006, all reconfiguring existing spaces.

In contrast to the Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian architecture still found in ‘Heart and Cathedral’, the architectural character of the ‘High Street and Castle’ area is firmly 20th century in origin, resulting from extensive post war clearance and renewal, within the existing framework of the earlier street pattern. This area was proposed for further redevelopment as a main node of the envisioned ‘Civic Circle’; Sheffield Replanned (Sheffield City Council 1945) originally intended that the ‘Civic Circle’, essentially a dual-carriageway road system, would continue along Church Street. Instead the ‘Circle’ terminated at the Hole in the Road, a starkly modernist subterranean shopping mall open to the sky, above which was a major roundabout. The site was backfilled in the early 1990s as part of the works to re-introduce a tram system to the city.

Figure 4: Tram at Castle Square – site of the former Hole in the Road. The buildings to the left are typical of the modern architecture that characterised the rebuilding of the heavily bombed ‘High Street and Castle’ area.

© Stephen McKay and licensed for reuse according to a creative commons license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Character Areas making up this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

Bibliography

- AHP (The Architectural History Practice)

- 2003 Sheffield City Centre Characterisation [unpublished]. Report for Sheffield City Council UDC.

- Belford, P.

- 2001 Work, space and power in an English industrial slum: ‘the Crofts’, Sheffield, 1750-1850. In: A. Mayne and T. Murray (eds.), The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes: Explorations in Slumland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 106-117.

- Belford, P.

- 2003 Advanced Art, Imperfect Science: The Archaeology of Cementation and Crucible Steelmaking in Sheffield 1700-1850. Ironbridge Archaeology Monograph 1. Oxford: BAR Archaeopress.

- Crossley, D. (ed.) with Cass, J., Flavell, N., and Turner, C.

- 1989 Water Power on the Sheffield Rivers. Sheffield: Sheffield Trades Historical Society with University of Sheffield Dept. of Continuing Education.

- Harman, R. and Minnis, J.

- 2004 Sheffield: Pevsner Architectural Guide. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Hey, D.

- 1998 A History of Sheffield. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing.

- Pollard, S.

- 1956 The Growth of Population. In: D.L. Linton (ed.), Sheffield and its Region: A Scientific and Historical Survey. Sheffield: British Association for the Advancement of Science.

- SCC (Sheffield City Council)

- 1945 Sheffield Replanned: A Report, with Plates, Diagrams and Illustrations, Setting out the Problems in Re-planning the City and the Proposals of the Sheffield Town Planning Committee. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council.

- SCC (Sheffield City Council)

- 2004 Sheffield City Centre: Urban Design Compendium [unpublished]. Report for Sheffield City Council prepared by Gillespies.