Municipal Suburbs

Summary of Dominant Character

Municipal suburban development, or what are more commonly referred to as ‘council estates’, can be divided into two general phases of development. The first is dominated by ‘garden suburb’ type estates, populated with two storey ‘cottages’ at a medium density within individual gardens. This type of housing can be found across the UK and was actively promoted by central government in the early to mid 20th century as an ‘ideal’ of suburban development for the working classes.

Figure 1: The edge of the ‘Herringthorpe, Eastwood and East Dene’ character area, showing typical inter-war council housing.

© 2005 SYAS

The second phase can be said to have begun to develop in the years following World War Two, with the economic realities of the post-war period requiring radical solutions to housing need. These solutions included the development of new ‘pre-fabricated’ construction techniques and moved on, through the 1960s and 1970s, to encompass higher density estate plans where private space was replaced by communal grassed, recreational areas and in, some areas, terraced forms were introduced along with new concepts such as the tower and maisonette block. Rotherham’s housing authorities were generally less messianic about the creation of radical modernist designs than their contemporaries in Sheffield, with only one notable tower block recorded in the Borough and the vast bulk of the municipal housing stock continuing ‘garden suburb’ type estate plans.

The early to mid 20th century parts of this zone are dominated by semi-detached houses and short terrace rows, laid out in geometrical patterns based on intersecting circles with open greens, institutional buildings and retail areas placed at the hubs of these radial streets. Culs-de-sac do occur, but most roads form circuits, and houses are generally aligned to a repetitive pattern, with small front and larger rear gardens. Public green spaces are generally simple areas of grass and there are few street trees included in the designs.

Until the late 19th century, house construction was the province of private individuals with land owners and industrialists responsible for most construction. From the 1840s there were increasing concerns over the standard of housing for the poorer parts of society (Havinden 1981, 417) and the beginnings of pressures for local authorities to intervene in matters of housing. In Rotherham, industrial growth and demographic shifts in population and living patterns had greatly increased the density of the historic core of the town by the mid 19th century, with most of the historic burgages having been intensified over the previous century by the construction of courts of small insanitary cottages within their back-lands.

Whilst the establishment of the Board of Health in 1852 and Rotherham Borough Council in 1871 allowed the process of improving the sanitary provision in the town to begin, notably by the improvement of the water supply and sewerage system (Munford 1995, 282), the local authority had little power until late in the century to directly tackle the issues around housing stock. The 1890 Housing of the Working Classes Act extended municipal bodies interests in housing beyond just rebuilding, to the establishment of new estates (Gaskell 1976, 187). Rotherham’s first response to the Act was small in scale. An initial plan to develop 60 houses was, by the time of its enactment, reduced to 10 houses at 59-77 Lord Street, although these were not characteristic of the present zone, having little to differentiate them from other very early 20th century housing (Munford 1995, 284).

Although there was a growing recognition that state intervention was required to solve housing problems, it was not until after the First World War that centralised government subsidies were focused on home building. ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ being a compelling slogan aimed at quelling public unrest by providing new low density houses for the expanding population (Short 1982, 31-2). The political will for change found its official expression in the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1919, which required all local authorities to organise building schemes for rapid completion. These schemes were partially financed from a local rate levy of 1d in the pound (Munford 1995, 284). Part of the outcome of this act was a detailed Parliamentary inquiry into the planning of new suburbs for the working classes, which produced the Tudor Walters Report (Whitehand and Carr 2001, 45). The research carried out for the Tudor Walters report fed into the production of the Local Government Board’s Manual on the Preparation of State Aided Housing Schemes of the same year – key recommendations being the provision of low to medium density estates of two storey cottages with three bedrooms, bathroom, parlour, living room and scullery. Rear projections, bay windows and excessive ornament were discouraged on the grounds of cost and also in the interest of providing “a clear view of the gardens” (ibid).

The first new municipal suburb in Rotherham was the ‘East Dene’ estate, built to the east of the town centre in 1919.

Figure 2: The ‘East Dene’ estate was the first to be built by Rotherham Council; its planning represents a direct implementation of the ‘Tudor Walters’ recommendations. Clear garden-suburb influences can be seen, including the medium density patter of cottages, the provision of ‘village greens’, and the concentric ‘picturesque’ curves of many of the roads.

Mapping based on the 1938 OS 6 inch mapping © and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 2008) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

The municipal housing schemes of the inter war years failed to solve existing housing problems. This, alongside the hiatus in construction during the Second World War, an increase in population, and war damage to existing housing, led to a severe shortage of houses. Radical answers to the housing crisis included the development of new ‘system building’ technologies. Early moves into this area were made by the National Coal Board in Aston, Kiveton Park and Dinnington, with the use of prefabricated concrete panels on the now demolished White City estates.

Rotherham Council built some high density but low rise block developments in central Rotherham - at St Anne’s Road Flats, erected in 1967 and demolished in 1987, and at Oakhill Flats at Eastwood, erected in 1971 and demolished in the late 1990s (Munford 2000, 138). However, the council seems to have largely eschewed the construction of high rise blocks, the notable exception to this being the ‘Beeversleigh’ block on Clifton Lane. This 15 storey (140m) hexagonal block features an unusual projecting concrete frame and was built in 1970-71 (ibid).

Figure 3: Beeversleigh Flats, Clifton Lane.

© Copyright Steve Fareham, used according to a Creative Commons licence [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/]

Relationships with Adjacent Character Zones

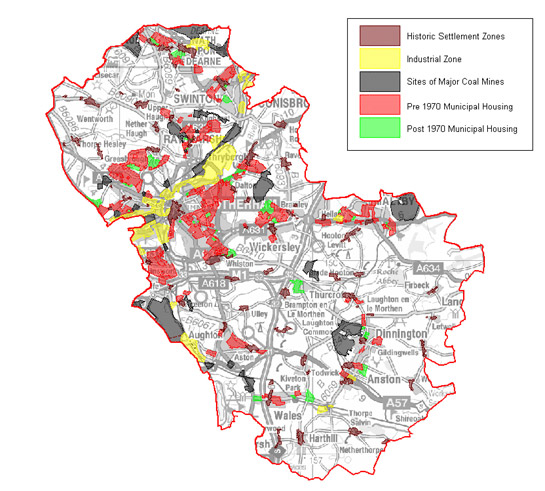

This zone is most clearly related to the historic location of industrial and mining activities in the district - which required large workforces. The largest concentration of municipal housing is situated along the Don valley, where many residents are likely to have been engaged in the metal trades.

Figure 4: Pre-1970 (red) and post-1970 (green) parts of the Municipal Suburbs character zone, shown in relation to related zones of activity.

Base mapping taken from OS 1:250,000 mapping © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007

Large areas of social housing are included within the ‘Planned Industrial Settlements’ zone, around the sites of the major twentieth century mines; the mining sector being an industry that had developed its own tradition of social housing provision, often independently and in advance of similar provision by local authorities. However, following the nationalisation of the mining industry in 1948, it becomes less clear which housing areas were provided by the NCB and which by Rotherham MBC.

Inherited Character

There is little visible of past landscapes within the larger council developments around Rotherham. The scale of development that allowed for the establishment of large geometric estate plans mostly overwrote the earlier field patterns. At the edges of these estates there are a few surviving boundary patterns, but often it is the main roads that are the main surviving feature of the earlier, rural landscape.

Later Characteristics

The 20th century saw large numbers of council homes built across the country; 1954-5 was the peak of council building and there followed a steady decline in numbers of houses built after that (Short 1982, 52). This trend was to draw to a close in the later part of the 20th century, as council tenants were encouraged to buy their homes and there were fewer government incentives for councils to build new social housing (ibid, 59). A number of council houses in Rotherham moved into private hands in this time. This is part of a nationwide trend where home ownership has increased and council renting decreased since the 1970s (Office for National Statistics 2004, 30).

This trend has led to more housing currently being built by private developers - a trend that has itself led to the development of large late 20th century suburbs. Within the ‘Municipal Suburbs’ zone there has been some infilling with privately built housing, as well as private expansion around them.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Aston Municipal (Map)

- Bramley and Listerdale Municipal (Map)

- Brampton and West Melton Municipal (Map)

- Brinsworth and Catcliffe Municipal (Map)

- Broom, Moorgate, Whiston and Canklow (Map)

- Dinnington and Anston Municipal (Map)

- Herringthorpe, Eastwood and East Dene (Map)

- Kimberworth Park Municipal (Map)

- Kingswood and Firbeck Avenues Laughton (Map)

- Kiveton Park and Wales Municipal (Map)

- Maltby Municipal (Map)

- Rawmarsh Municipal (Map)

- Richmond Park and Blackburn Municipal (Map)

- Swinton Municipal (Map)

- Thrybergh Municipal (Map)

- Thurcroft Municipal (Map)

- Treeton Municipal (Map)

- Wath/ Bow Broom Municipal (Map)

- Whinney Hill and Dalton Municipal (Map)

- Wickersley Municipal (Map)

- Wingfield and Greasborough Municipal (Map)

- Woodhouse Mill Municipal (Map)

Bibliography

- Edwards, A.M.

- 1981 The Designs of Suburbia. London: Pembridge Press.

- Gaskell, S.M.

- 1976 Sheffield City Council and the Development of Suburban Areas Prior to World War I. In: S. Pollard, and C. Holmes (eds.), Essays in the Economic and Social History of South Yorkshire. Sheffield: South Yorkshire County Council, 187-202.

- Havinden, M.

- 1981 The Model Village. In: G.E. Mingay (ed.), The Victorian Countryside, Volume II. London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 414-427.

- Munford, A.

- 1995 From Slums to Council Houses: The Rotherham Experience. In: M. Jones (ed.), Aspects of Rotherham. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books, 273-297.

- Munford, A.

- 2000 A History of Rotherham. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

- Office for National Statistics

- 2004 Living in Britain: Results from the 2002 General Household Survey [online]. The Office for National Statistics. Available from: www.statistics.gov.uk/lib2002/ [accessed 01/04/08].

- Short, J.R.

- 1982 Housing in Britain: The Post War Experience. London and New York: Methuen.

- Whitehand, J.W.R and Carr, C.M.H

- 2003 ‘Twentieth Century Suburbs’ in Urban Morphology 7:1