Surveyed Enclosure

Summary of Dominant Character

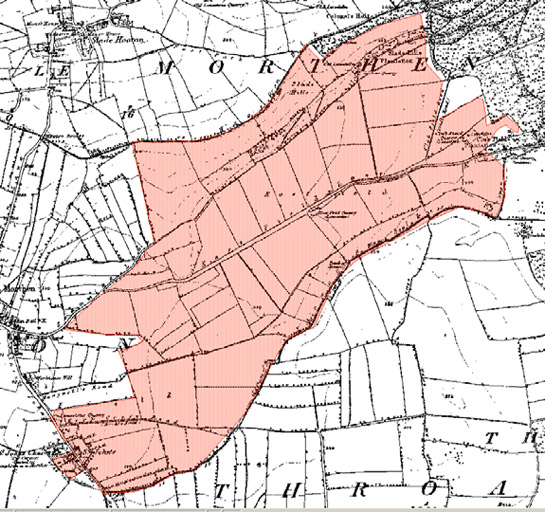

Figure 1: Looking towards the village of Laughton en le Morthen across land enclosed from Laughton Common by Parliamentary Award in 1771.

© SYAS 2006

This zone is characterised by land enclosed by straight-sided hedgerows laid out to a regular pattern. Roads within the field pattern are often straight and of a standard width (Hindle 1998), complimenting the overall design of the landscape. Woodland is often characterised by plantations, either planned deliberately as part of the surveyed layout or planted later within existing surveyed enclosure boundaries. In Rotherham, however, there is also a significant amount of older ancient woodland, typically occupying steep ground or related to historic common land.

Surveyed enclosure mostly dates to the 18th and 19th centuries, but there are also some more recently redesigned areas of straight sided enclosure, which are included within the zone. The initial enclosure of this land typically took place through the allocation of open field units and grasslands formerly held in common to privately held hedged holdings during the 18th and 19th centuries, often under the authority of a parliamentary award.

The process of enclosing areas of commons and communally farmed open or town fields had been occurring long before the 1700s (Hey 1986, 192). When done by the agreement of the local population this often led to the development of piecemeal, irregular enclosure patterns (see ‘Assarted Enclosure’ zone). By the 18th century, the call by large landholders to enclose land was supported by Acts of Parliament; where owners of three quarters of the land agreed, an Act could enforce their wishes upon the minority landholders (ibid, 193). This often meant that the poorest farmers fared badly. This division of land was the creation of a surveyor’s drawing board and led to a very regular field pattern.

Figure 2: The regular fields within the ‘Slade Hooton Surveyed Fields and Laughton East Field’ character area, of former open fields enclosed by the 1771 Laughton en le Morthen and Slade Hooton Enclosure Award, contrast with the more vernacular piecemeal strip enclosures of earlier private arrangements nearby.

© and database right Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Ltd (All rights reserved 200X) Licence numbers 000394 and TP0024.

Farmsteads within the zone generally align with the field system, indicating a contemporary or later date. This is supported by the fact that their plan form principally corresponds to the ‘courtyard’ plan type. Characterisation of farmstead types in Yorkshire has revealed that farms based around regular planned courtyards “were most commonly developed on arable based farms established as a result of enclosure from the later 18th century” (Lake and Edwards 2006, 44).

The areas of more modern enclosure within this zone date to the mid to late 20th century and are generally the result of re-instatement of land to agricultural use after opencast coal working or deep shaft coal mining. There are broad similarities between some of these areas and areas of ‘Surveyed Enclosure’ enclosed by parliamentary award. The main difference lies in the nature of the hedgerows dividing up the land. In areas of re-instatement, hedges are less mature and contain few trees, although there are sometimes small plantations along the edge of the fields. These were probably planted at the time of mineral extraction, to mask the works from nearby roads and houses.

Relationships with Adjacent Character Zones

The ‘Surveyed Enclosure’ zone can be found across the rural areas of Rotherham, typically alternating with landscapes of the ‘Strip Enclosure’ and ‘Agglomerated Enclosure’ zones. The boundaries between ‘Agglomerated’ and ‘Surveyed’ enclosure zones are often difficult to identify on the ground, as both have generally been subject to high levels of boundary removal; key indications of the ‘Surveyed Enclosure’ zone are the absence of curving boundaries within surviving boundaries.

A significant proportion of character areas in the ‘Industrial Settlements’ zone were developed on land enclosed by Parliamentary Award from former grassland commons.

Inherited Character

The areas of parliamentary enclosure within this zone represent a large-scale systematic programme of landscape design and change. This process involved dramatically altering the character of an area in social as well as physical terms, as former common resources were transformed into private land only accessible to its owners and tenants. The physical transformation of the land involved, for the most part, a complete change from what was already present. In some grassland common areas this meant the land was ploughed for the first time (Taylor 1975, 143) and where lime was added to the land this altered the plant species that could grow there.

It is likely that the enclosure and subsequent agricultural use of common lands in the borough significantly reduced the legibility of earlier landscape activity. Where land had not previously been ploughed, prehistoric and earlier historic monuments may have survived as upstanding mounds, ditches and banks; such monuments are known to have been destroyed by agricultural improvement programmes following parliamentary enclosure in the nearby Doncaster ‘Surveyed Enclosure’ zone.

While agricultural improvement is likely to have removed many archaeological traces of earlier activities on historic common lands, two character units within this zone do have significant legibility of former historic common landscape types. Wood Lee Common in Maltby appears to have avoided agricultural improvement, historic maps indicating it has retained a covering of rough ground since at least 1775. The area is now designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) on account of its outcropping Magnesian Limestone bedrock, which supports rare species rich grassland habitats (Rotherham MBC 2003). A more complex former grassland common landscape is still legible at Lindrick Common Golf Club, which was adopted as a golf course directly from former common use in 1891. In addition to significant areas of species rich grassland flora (for which the site is notified as an SSSI), a number of relict post-medieval industrial features can also be seen here, including quarries and kiln structures.

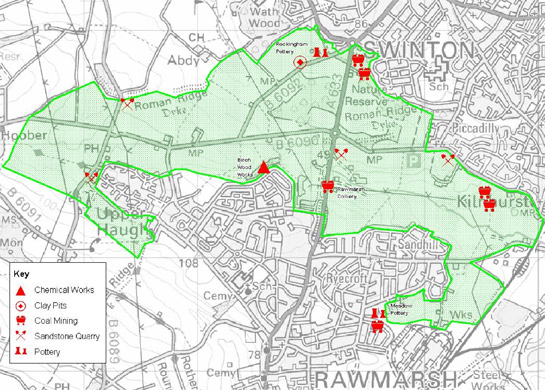

Traces of the post-medieval landscape of Rotherham common lands are also well expressed within and around the ‘Rawmarsh and Swinton Commons’ character area. This area includes a number of relict industrial features, including the nationally important remains of the Swinton / Rockingham Pottery (SMR ref: 2218), the Warren Vale Colliery and the Birch Wood Chemical Works and a number of sandstone quarries and coal pits depicted on mid 19th century mapping as ‘old’.

The recorded history of the Swinton Pottery, in particular, captures the extent to which this common land was already being exploited for industrial purposes prior to its enclosure in 1776, 1781 and 1820 (dates from English 1985). The pottery dates back to at least 1745 (Cox and Cox 1970), when a Joseph Flint was recorded as renting property on Swinton Common for digging clay, operating a brickworks, tile yard and pot house (Bell 2002b). The pottery was chiefly concerned with the production of earthenware until a financial crisis led to the potteries rescue by Earl Fitzwilliam in 1825 (ibid, 2). The renamed Rockingham Pottery diversified production to include porcelain, which would make it internationally famous. The works was sold in 1843, when pottery production ceased, but the works continued to decorate the products of other potteries until 1865.

Figure 3: ‘Swinton and Rawmarsh Commons’ character area, showing the sites of industrial activity depicted on the 1854 OS map.

(Based on 2003 OS 1:25000 map base © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Sheffield City Council 100018816. 2007)

The remaining buildings at the pottery site consist of: Flintmill Farm, which dates to the late 18th century when "it served as a working farm, providing stabling for draught horses and including willow garths and plantations of crate wood [providing] packaging materials" (EH Scheduling description); a bottle kiln; Strawberry Farm (thought to be part of the main works complex depicted in 1855 and demolished by 1894); internal land divisions and extraction pits (now ponds) shown in 1855, and the surrounding plantation woodlands. The present layout closely relates to the appearance of the site on 1894 mapping, by which time much of the works had been demolished.

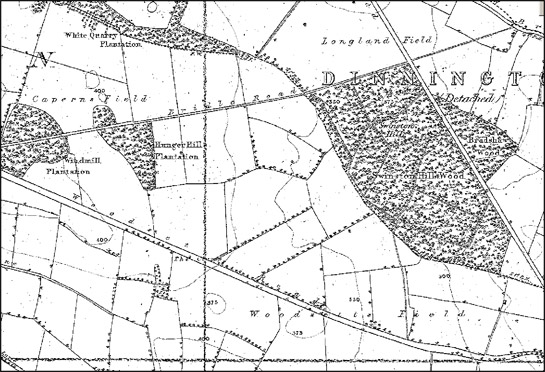

A significant proportion of this zone previously consisted of open townfields. These were large medieval fields that surrounded a nucleated settlement and were divided into unhedged strips, which were individually owned but farmed in common. Parliamentary enclosure here has left a more complex pattern of historic legibility, when compared with the former commons. In many cases, former open field names are shown on Ordnance Survey mapping, although they are associated with a number of modern land parcels (Oliver 1993, 56). In some cases parts of these former open fields remain legible – particularly the boundaries of the medieval open fields, relict strip boundary features and older lane patterns.

Figure 4: The 1850s edition of the OS 6 inch to the mile survey of Yorkshire often indicates former open field names, as in this extract within the ‘Surveyed Former Open Fields East of Dinnington and North Anston’ character area.

Image © Sitescope Ltd

Later Characteristics

Much of this zone has seen significant boundary loss in the second half of the 20th century. This process has continued into the present, as the economies of scale provided to farmers by larger land parcels continue to offer incentives to remove hedges. At farmstead sites this intensification has been accompanied by continued investment in larger buildings, typically sheds built from prefabricated materials, less indicative of their function or local origins than earlier farmstead components.

These processes have tended to produce a landscape with many similarities to the ‘Agglomerated Enclosure’ zone, but the relict features of each zone (for instance the straightness or otherwise of their field boundaries) serve to differentiate their separate origins.

Acting to counter these trends are incentives offered by the ‘stewardship’ schemes sponsored by central government since the early 1990s. These schemes offer financial incentives to farmers who enter into environmental management agreements, which can include steps to maintain or restore historically characteristic features such as boundaries, buildings and (under the Environmental Stewardship system in place since 2005) reduce the impact of their activities on known buried archaeological sites (Rural Development Service 2005, 68-70).

A contemporary development has been the introduction of the Hedgerow Regulations of 1997 (HMSO). This requires the notification of the Local Planning Authority before the removal of a hedgerow, in addition to conferring powers on the same authority to serve a “Hedgerow Retention Notice” where hedgerows can be defined as important in historical, archaeological, wildlife or landscape terms.

One of the most difficult later developments to trace within this landscape is the effect of reinstated open cast mining. The Middle and Upper Coal Measures make up most of the underlying geology of Rotherham and a number of coal seams run close to the surface here. These became the focus of attention for the Directorate of Opencast Mining from the Second World War onwards (Gray 1976, 41). Running through this bedrock there are also rich seams of clay that have been utilised for pottery and brick production over the years. Since the late 20th century these resources have been extracted on a larger scale, in opencast pits. After the closure of areas of opencast clay or coal mining the land is often reinstated with new field boundaries, which tend to be regular and straight, a good example being in the ‘Cinder Bridge Field and West Hill Field, Greasborough’ character area. Where reinstatement of the land has been successful there is often no clear sign of the opencast mining itself. The key difference is that these hedges tend to less diverse than earlier ones, with few mature trees.

Transportation routes have made significant impacts on the landscape of Rotherham. As the industries of the borough developed, large numbers of railway lines were laid across the landscape, cutting across earlier field boundaries. Despite the closure of most of these lines and the removal of their tracks their earthen embankments and tree lined sides stay as clear reminders of former industrial landscape.

The railways of Rotherham have been dramatically reduced in number since the late 20th century, but the continuing effect of transport is seen in the construction of roads though the district. The M18 motorway cuts through part of this zone, as do other modern duel carriageways. Their dominant constructional materials are concrete, steel and massive earthen embankments, which generally sever earlier previously coherent landscape units. The gentle curves of these roads are in direct contrast with the straight lines of earlier roads and boundaries within this zone.

Character Areas within this Zone

Map links will open in a new window.

- Aston Common (Map)

- Braithwell and Ravenfield Commons (Map)

- Brinsworth Nursery (Map)

- Cinder Bridge Field and West Hill Field, Greasborough (Map)

- Coal Riding Lane, Dalton Magna (Map)

- Surveyed Former Open Fields East of Dinnington and North Anston (Map)

- Far Field, Wath upon Dearne (Map)

- Green Royds Moor, Whiston (Map)

- Former Open Fields at Hooton Roberts (Map)

- Kingsforth Field Surveyed, Wickersley (Map)

- Laughton Common (Map)

- Lindrick Common and Fan Field, South Anston (Map)

- Surveyed Enclosure around Maltby Wood (Map)

- Nether Field, Guilthwaite Common and Turnshaw Common, Ulley (Map)

- Rawmarsh and Swinton Commons (Map)

- Simon Wood and King's Wood (Map)

- Slade Hooton Surveyed Fields and Laughton East Field (Map)

- Todwick Common and Conduit Moor or Common (Map)

- Wentworth and Harley Surveyed Enclosures (Map)

- Windmill Hill, Harthill (Map)

- Woodhall Common, Thorpe Common, Hard Field and Loscar Field (Map)

Bibliography

- Bell, S.

- 2002 Archaeological Field Evaluation within SAM 29957, Swinton Pottery, Blackamoor Lane, Swinton, South Yorkshire [unpublished]. Sheffield: ARCUS.

- Council for British Archaeology

- 2003 Defence of Britain Database [online]. Available from: http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/resources.html?dob [accessed 20/02/08].

- Cox, A. and Cox, A.

- 1970 The Potteries of South Yorkshire. The Antique Dealer and Collectors Guide, Nov 1970.

- English, B.

- 1985 Yorkshire Enclosure Awards. Hull: University of Hull.

- HMSO

- 1997 The Hedgerows Regulation (Statutory Instrument 1997 No.1160).

- Hey, D.

- 1986 A Regional History of England: Yorkshire From AD 1000. London: Longman.

- Hindle, P.

- 1998 Roads that ramble, and roads that run. British Archaeology, 31 [online]. Available from: http://www.britarch.ac.uk/ba/ba31/ba31feat.html [accessed 20/02/08].

- Hunter, J.

- 1831 South Yorkshire: Volume 2. Sheffield: Pawson and Brailsford.

- Large, J.S.

- 1952 A History of Barnburgh. Mexborough: Russells Ltd.

- Rotherham MBC

- 2003 Wood Lea Common [sic.]SSSI [online]. Available from: www.rotherham.gov.uk/graphics/Leisure/Countryside+and+Wildlife/Sites+of+Special+Scientific+Interest/EDSWoodLeaCommon.htm [accessed 14/04/2008].

- Rural Development Service

- 2005 Higher Level Stewardship.

- Taylor, C.

- 1975 Fields in the English Landscape. London: J.M. Dent and Sons Ltd.

- Lake, J. and Edwards, B.

- 2006 Historic Farmsteads. Preliminary Character Statement: Yorkshire and Humber Region. Cheltenham: University of Gloucester/ English Heritage/ Countryside Agency.

- Oliver, R.

- 1993 Ordnance Survey Maps: a Concise Guide for Historians. London: Charles Close Society for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps.